"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

08/19/2020 at 09:05 ē Filed to: good morning oppo, wingspan

4

4

12

12

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

08/19/2020 at 09:05 ē Filed to: good morning oppo, wingspan |  4 4

|  12 12 |

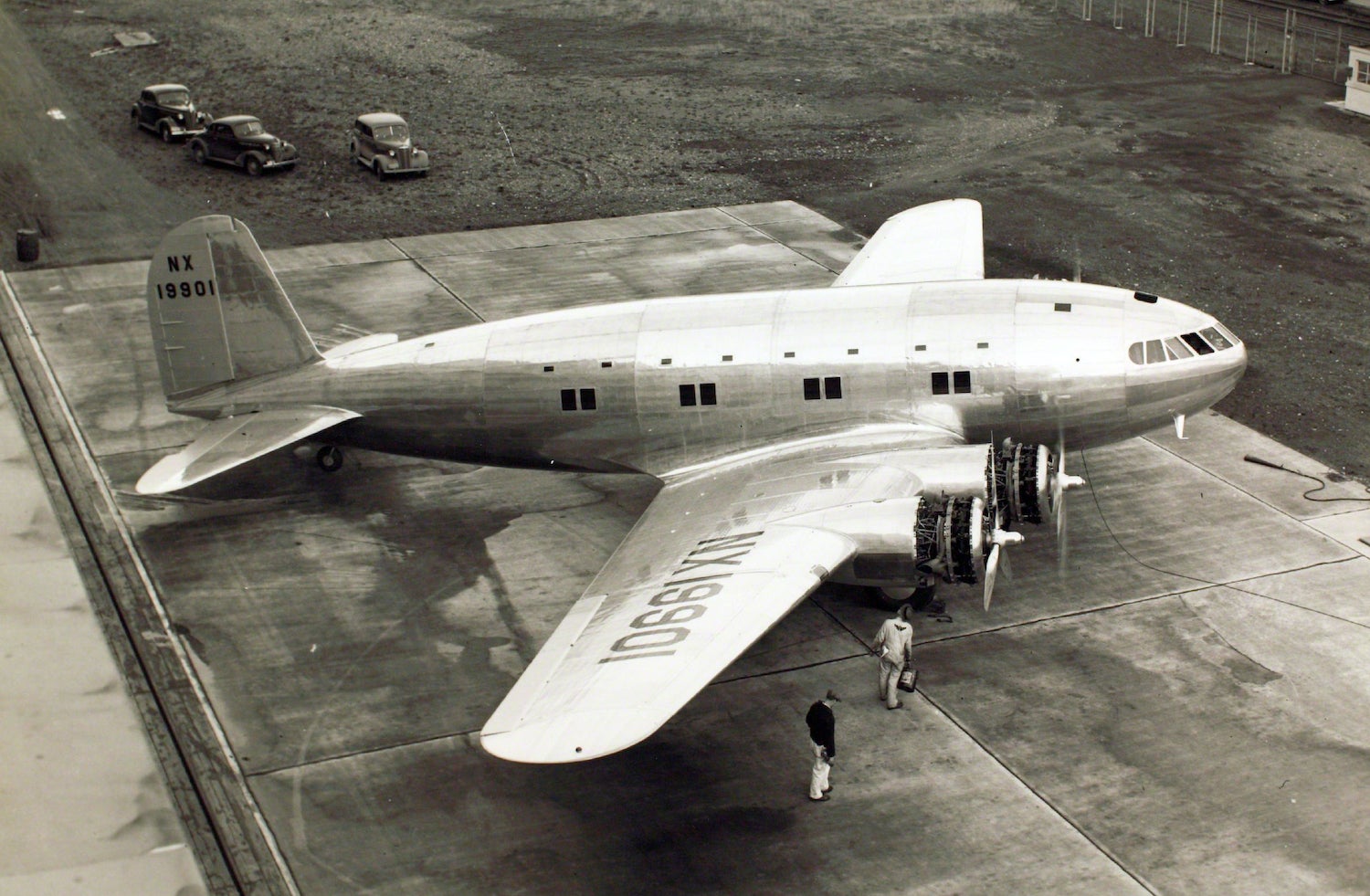

For Wednesday, we have the first Boeing 307 Stratoliner, which bridged the gap from the end of the Golden Age to the end of WWII.

Sharing the wings, engines, landing gear, and tail of the B-17C bomber, the Stratoliner received an enlarged circular fuselage and pressurization, a first for its day. The 307 was poised to make major inroads into the airline industry, but the outbreak of WWII saw Stratoliner production shift to the military transport version, which was called the C-75. The aircraft in the top photo, NX19901, was the first Stratoliner every built, but it was not a prototype, as Boeing planned to turn the airliner over to Pan American after testing. During a test flight to pitch the 307 to KLM executives, the aircraft entered a spin and !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , killing all 10 onboard. The cause of the accident was traced to !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , and subsequent C-75s, and B-17s, were modified by extending a dorsal fin in front of the vertical stabilizer. Only ten 307/C-75s were built, and the sole survivor is kept in flying condition at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington DC.

Maxima Speed

> ttyymmnn

Maxima Speed

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 09:16 |

|

Thatís a beautiful plane, i think it might be my new† favorite commercial passenger plane.†

ttyymmnn

> Maxima Speed

ttyymmnn

> Maxima Speed

08/19/2020 at 09:35 |

|

The world needs more shiny aluminum planes.

facw

> ttyymmnn

facw

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 09:52 |

|

I continue to be amazed that this aircraft flew to Dulles:

Itís a gorgeous plane even under water though.

Also Iím sad that I canít find a higher-res picture of this:

ttyymmnn

> facw

ttyymmnn

> facw

08/19/2020 at 10:25 |

|

I would be interested to see what it looked like right after they pulled it from the water. I read the Seattle PI story about the ditching. They simply ran out of gas. I donít know if any official blame was laid for that. I suppose itís good that the pilot ditched rather than try to bring it down on land. Maybe the damage was less severe than it could have been?

user314

> ttyymmnn

user314

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 10:26 |

|

*nods*

Things started falling apart when they started painting airplanes.

facw

> ttyymmnn

facw

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 10:31 |

|

They probably didnít have much choice. There isnít really any open fields in that area, everything is densely built, or on the west side of the bay, sometimes heavily forested. But the land is generally neither flat nor open. If they couldnít reach Boeing Field, SeaTac, or Renton, the water was basically the only place to put it.

Bonus fun fact: Boeing claims that level the area for the construction of Paine Field, they had to move †more earth than for the construction of the Panama Canal.

ttyymmnn

> user314

ttyymmnn

> user314

08/19/2020 at 10:34 |

|

I even miss the last AA livery. Sure, it was getting a little tired maybe, but those stripes sure popped against the silver.

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 14:01 |

|

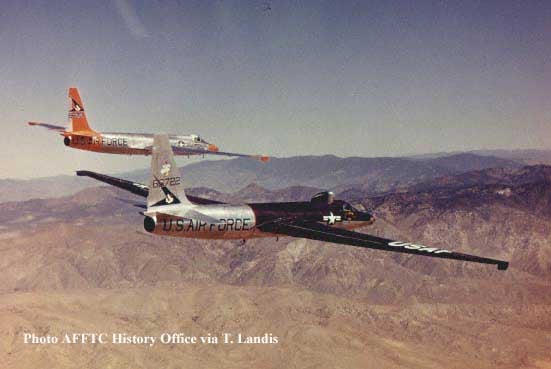

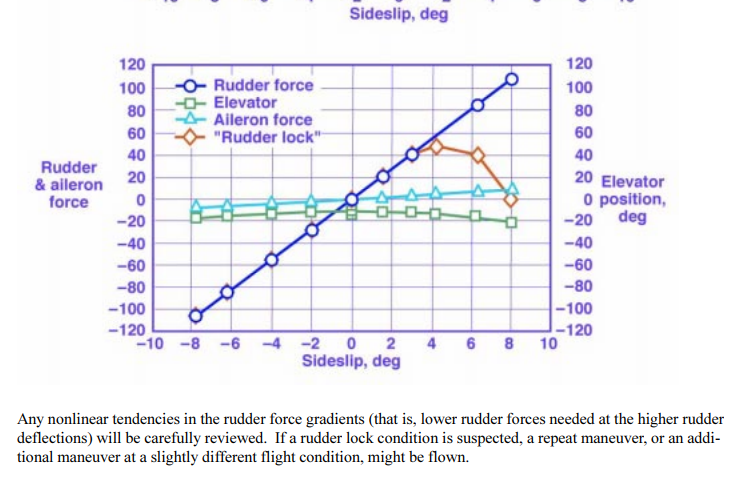

Interesting that I learned about rudder lock from your link . Boy is that a diabolical failure. Worth an article in itís own to explain what is happening,

ď The vertical stabilizer often employs a small fillet or ďdorsal finĒ at its forward base which helps to increase the stall angle of the vertical surface (thanks to vortex lift) and to prevent a phenomenon called rudder lock or rudder reversal. Rudder lock occurs when the force on a deflected rudder (in a steady sideslip ) suddenly reverses as the vertical stabilizer stalls. This may leave the rudder stuck at full deflection with the pilot unable to recenter it. [2] Ē

Here is the link for below drawing

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

ttyymmnn

> RacinBob

ttyymmnn

> RacinBob

08/19/2020 at 14:09 |

|

Iím not enough of an engineer to write intelligently about it, but I do think I have a little bit of a knack to learn just enough about something to put it in laymanís terms. Re: rudder lock, I always wondered why the tail of the B-17 changed from the prototype to the later production bomber. I learned that for myself with this 307 post.

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 16:06 |

|

Ahaó-Brilliant when you see the difference in a picture. I think the story is that if say the tail is spinning towards you the tail being presented sideways to the airflow no longer has air flowing along it and as a result the movable rudder has no longitudial airflow to direct.

If you look at the prior graph, that is why at 4 degrees slip all the sudden the rudder force drops to zero. With no force, there is no longer a rudder effect meaning other than the drag of the tail there is nothing to keep the tail of the plane from keeping on rotating into a spin.....

Now in normal flight this might not be noticed as the drag of the tail tends to correct things. But if the test pilots were showing off, the pilot might have gotten into a spin that with the tail stalled it would not overcome. By the way these were high altitude planes so this may be a new problem that they had not had to deal with at 12,000 feet or below..

They called it a dorsal fin but I would say the extended faring into the tail. The extended faring solves this by forcing air to travel down the fuselage in a linear fashion, rather than allowing the air to spill sideways over the fuselage during slip angles. This air then continues to move to the tail and movable rudder which then means the rudder continue to do its job and presents force to full deflection.

So this fared rudder was a design feature of the B17 had a purpose much more than the casual observation suggests.

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

RacinBob

> ttyymmnn

08/19/2020 at 16:08 |

|

Now that I look I see a similar solution for the B29

ttyymmnn

> RacinBob

ttyymmnn

> RacinBob

08/19/2020 at 16:16 |

|

And you see that feature† on just about all aircraft of the period, and even modern jet airliners.†