"No, I don't thank you for the fish at all" (notindetroit)

"No, I don't thank you for the fish at all" (notindetroit)

09/13/2015 at 11:59 • Filed to: supercarriers, aircraft carriers, and stuff

4

4

3

3

"No, I don't thank you for the fish at all" (notindetroit)

"No, I don't thank you for the fish at all" (notindetroit)

09/13/2015 at 11:59 • Filed to: supercarriers, aircraft carriers, and stuff |  4 4

|  3 3 |

Inspired by !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , which is just chock full of what’s now considered to be floating, steel-forged anachronisms. But man, aren’t they iconic anachronisms or what? Nuclear-powered cruisers which seemed like the big, atomic-age idea at the time but were quickly retired as soon as the “Evil Empire” disappeared and with it the justification of their massive costs in money and manpower; frigates period , a classification of vessel that barely, if at all, even exists in the USN anymore; the once ubiquitous “ !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! ” which at the time was considered perhaps the most advanced non-aviation surface vessel afloat and formed the mold almost every Western-legacy naval vessel follows to this day, !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! ; and of course and most obvious of all the “big gun” battleship Mighty Mo. All of these form a fleet around a more subtle and easily missed icon that’s just as much a relic as the rest of the fleet - the “center-island” aircraft carrier.

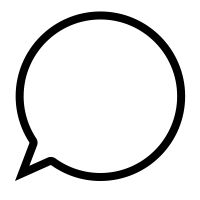

HMS Argus in the foreground, Public Domain via Wikipedia

When the aircraft carrier was new, it was simply a matter of putting the biggest take-off/landing platform possible onto whatever vessel you happen to be putting it on. In most cases it was a little deck on top of a battleship’s turret barely big enough to actually hold the plane - the plane by the tiniest slip of God had enough speed and room to take off, while landing was accomplished by having the pilot intentionally crash his plane near the ship, pluck the poor bastard out of the water and write off the cost of the plane as yet another war expense. Later on someone came up with the idea of putting floats on that plane because, maybe, reusing it and not having to fish its pilot out of the water after every flight might be something worth looking into. In other cases, it was going towards the other extreme and lopping off the entire top superstructure of the ship to fit a “flying platform” covering the whole damn thing, such as in the case of perhaps the first practical aircraft carrier, HMS Argus. Originally a relatively fast ocean liner, it got its top lopped off in favor of all the characteristics we would now classically associated with an aircraft carrier, all thanks to this one archetype - except for the “island.” Instead, the bridge was relocated to the very front just under the spot where planes would cut their Earthly (or is that Shiply?) bounds, and aircraft operations were still considered simple enough to not need anything beyond deckhand signals.

Almost immediately, even the slow fabric-and-wood biplanes of WWI had performance outstripping what deckhands can safely direct, plus having all of your ship’s navigational operations be conducted underneath a giant platform with the huge bow obstructing your vision really wasn’t ideal. To further create as much of an unobstructed flying platform as possible, a ship’s funnels were little more than vents cut directly into its side, not unlike how you’d perhaps imagine the ultimate sidepipe setup on whatever ultra-fast cruise ship or luxury liner you can imagine hotrodding !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! -style. As it turned out this really wasn’t ideal either; it turns out there’s a reason why funnels tend to be very tall structures, and the ship’s exhaust (which, mind you, was still a byproduct of coal or comparatively crudely refined oil combustion at this point) frequently blew across the deck for all of the deckhands, pilots and aircraft engine carburetors to ingest. Fun!

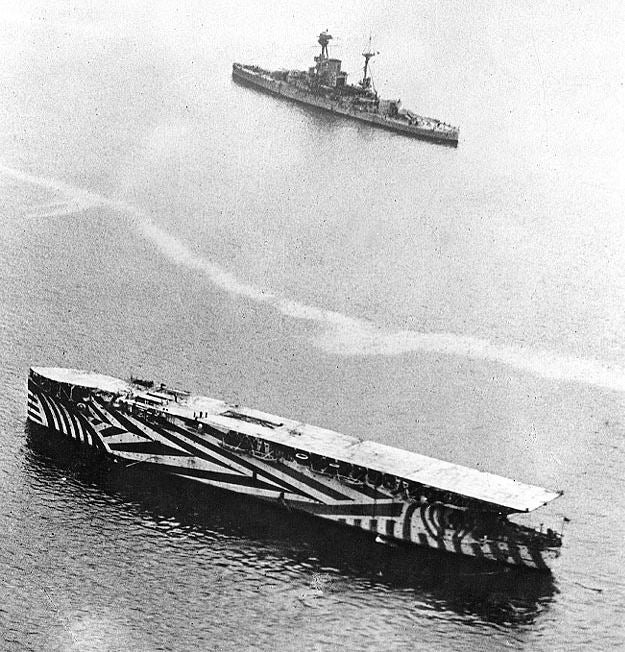

HMS Hermes, public domain via Wikipedia

After this “fun” experimentation period, it became clear that some sort of structure was needed to help direct aircraft operations - quite literally, slap a control tower in the middle of the ship. As such, it needed to be a very high vantage point. And, hey, what do you know, a very high vantage point also happens to be very useful when you’re actually trying to steer the ship itself, so put the ship’s bridge on it too. And hey while you’re at it maybe you can weld a giant funnel stack to it too so the crew wouldn’t have to worry about getting Black Lung Disease anymore. And so aircraft carriers such as HMS Hermes , the first ship built from the keep-up as an aircraft carrier, started spouting structures or “islands,” so called for, well, obvious reasons considering the otherwise completely featureless decks they sit on.

Naval planners and engineers learned a lot about aircraft operations in a hurry, so the design and placement of islands was never an accident or haphazard to begin with as they already collected all the data they needed to make intelligent decisions. For example, almost every single design included the island on the starboard (right) side of the ship, because wind patterns over the deck combined with the torque factor of an aircraft’s spinning propeller tended to pull landing planes towards the port (left) side - so having the island on the opposite side meant it less likely for a plane to smack into it. The main exceptions being about two or so Japanese carriers that would end up all getting sunk at the Battle of Midway; the thinking being that carriers with opposing islands would be paired with each other in very close formation with the port-island carrier doing all the launching operations and the starboard-island carrier doing all the recovery ops, but it turned out to be much too elaborate a plan to execute under real conditions. Then there was !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! with its - yes, island right down the centerline as a consequence of it being a very hastily converted cruiser, but that was a freak anomaly that was later converted into a more proper full right-island carrier. The only other real island-placement variation was how far fore or aft the island should be placed - putting it more forward was better for seeing where to steer the ship, but putting it closer to the stern was more beneficial for aircraft ops as it allowed a full, unobstructed view of all aircraft movement on the deck as well as for seeing approaching aircraft on landing. The most obvious compromise solution was to just place the island smack dab in the middle equidistant from stem to stern, which is exactly what most design drafters settled on. The fact that this also made for the easiest means to route funnel piping from the engines helped seal the deal.

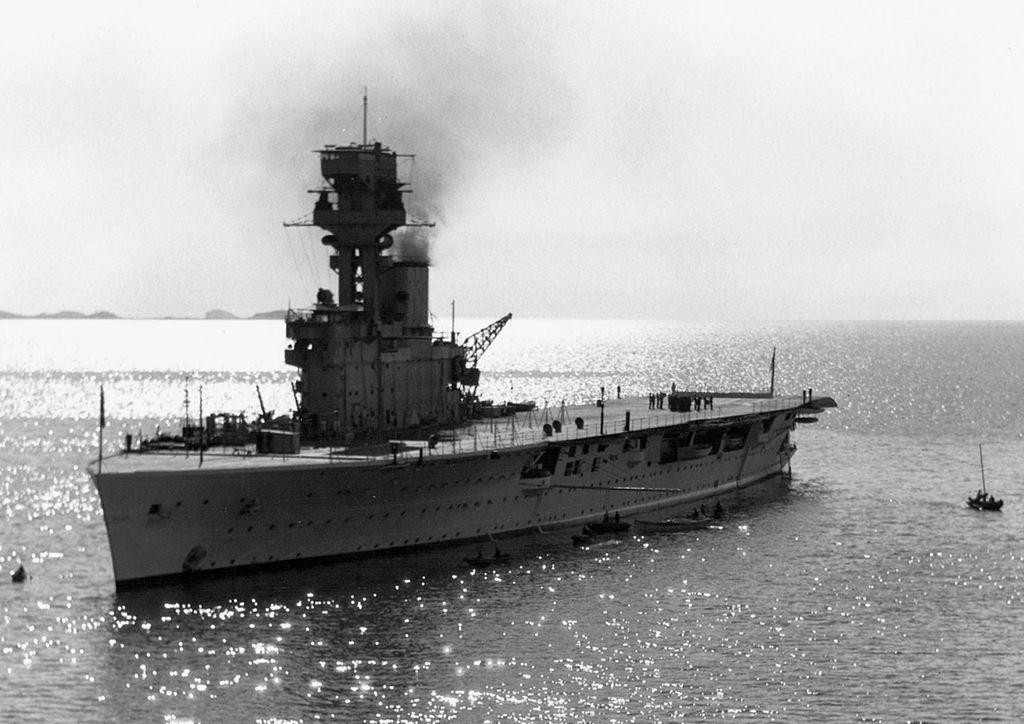

USS Oriskany during final cruise in 1976, public domain via Wikipedia

Through the next World War and into the Cold War and Supercarrier era, this was the firm model of how aircraft carriers looked like. Ernie Pyle, considered to be the finest war correspondent of WWII and perhaps of all time, !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! - except for its looks:

It lacks almost everything that seems to denote nobility, yet deep nobility is there. The carrier has no poise, no grace; it is top heavy and lop-sided; it has the lines of a well-fed cow; it doesn’t cut through the water like a cruiser knifing romantically along,; it doesn’t dance and cavort like a destroyer. It just ploughs. You feel it should be carrying a hod rather than wearing a red sash. Yet the carrier is a ferocious thing, and out of its heritage of action has grown it nobility.

Poise or grace aside, there’s a certain geometric aesthetic to a “classic” aircraft carrier - a clean hull leveled by a featureless plain topped off with an island that looks to be designed with a straight edge and absolutely nothing more sitting near-perfectly centered. That was the defining aesthetic of the Essex class, the most common “king-size” carrier of the USN or anywhere in the world from the Pacific Campaign to the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. and carried over to the Midway class, the first “supercarriers.”

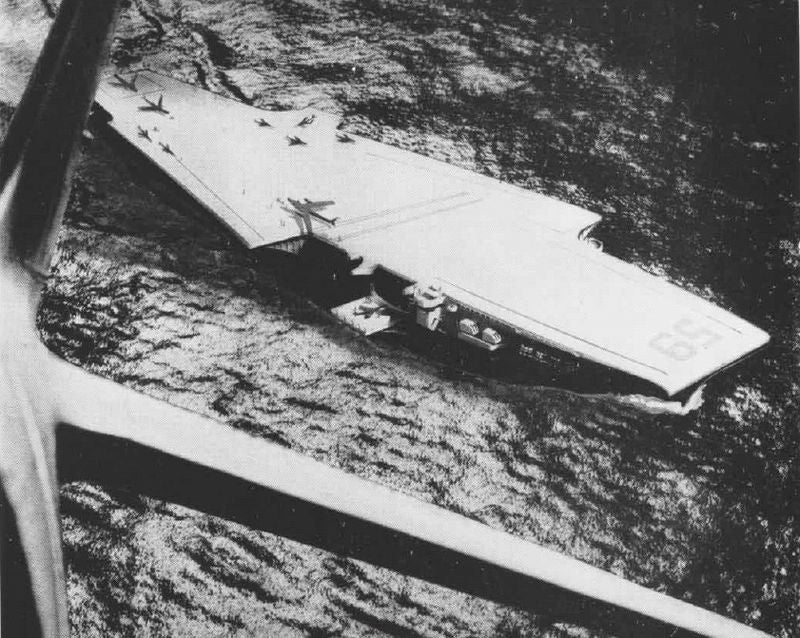

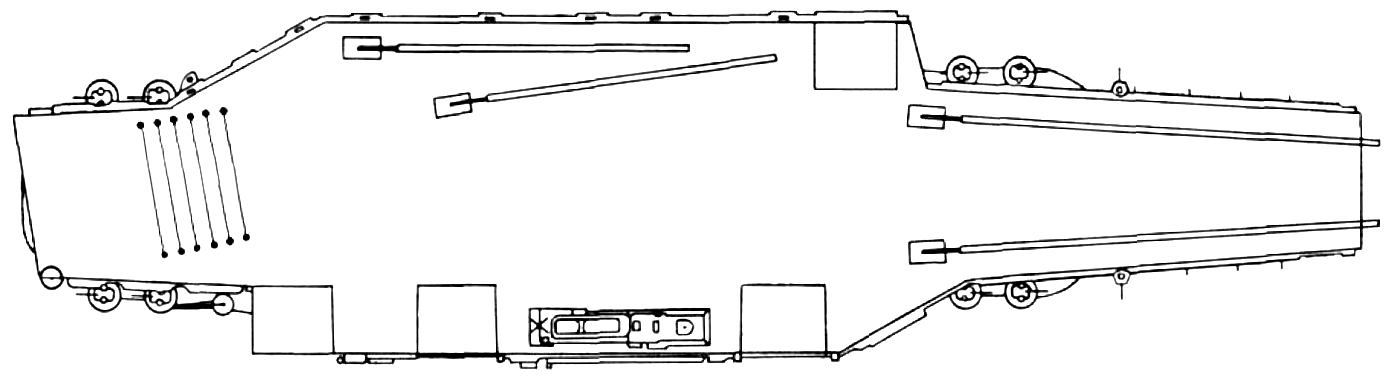

The original Forrestal-class design study, Public Domain via Wikipedia

Again, with the birth of this new unprecedented size of warship, it was thought to dispense with any kind of superstructure whatsoever for more efficient aircraft operations - and again, all actual ship navigation and related ops would be shoved to the bow under the flight deck or off to a tiny side structure practically invisible unless the blueprints happen to be right in your face, and a retractable island would pop up when needed to direct aircraft. This return-to-origins concept almost became realized in the stillborn USS United States , its story and cancellation worthy of its own multi-part essay, and in the USS Forrestal , a vessel actually built and the lead ship in the second class of supercarriers ever. Just as they had discovered some 30 to 40 years earlier, they ultimately decided that such fancy retractable structures were more trouble then they were worth and Forrestal was finished off with a conventional, centered island structure. Forrestal and her sisters were hardly the last carriers to have such large islands, but they would more or less be the last to share this once defining characteristic placement.

HMS Queen Elizabeth outfitting, Official Ministry of Defense photo via Wikipedia

Changes and further refinement in aircraft ops and ship interface meant one so far last and subtle (or not) evolution to the shape of the aircraft carrier - the island was no longer confined to the perfect center of the ship anymore as designers no longer had to settle for the “best compromise.” The British adopted decompartmentalized engine rooms so the gas turbines weren’t in the same vicinity (and thus wouldn’t all be knocked out after a single critical hit) necessitating two separate funnels and a looong island, particularly on the Falklands War-era “Harrier Carriers.” For the Queen Elizabeth class carriers the long connecting structure was eliminated altogether, with a forward island handling all the ship and fleet ops and a rear island handling all the aircraft ops. On American nuclear carriers, the need for funnels is eliminated completely. And they’ve just gotten so big and large - 100,000+ tons considered the norm - the attitude has pretty much become screw it, everybody else just better get out of the way - navigation is now completely taken over by tugs in tight spaces and on the open ocean, everybody just keeps clear of the Really Big Fish in the Really Big Ocean. Starting with the !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , islands on American supercarriers started creeping closer and closer to the stern - the ideal placement for aircraft-watching - with the !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! having it about as far back as you can shove it without falling off. With the last Forrestal rusting away waiting for either the scrapheap or some sort of alternative use, all supercarriers now pretty much look just a little lopsided with their rear-biased islands.

Hey, at least it might mean a little extra traction on the propellers during the winter months.

gmporschenut also a fan of hondas

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

gmporschenut also a fan of hondas

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

09/13/2015 at 12:09 |

|

“ Hey, at least it might mean a little extra traction on the propellers during the winter months.” Post of the day

My X-type is too a real Jaguar

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

My X-type is too a real Jaguar

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

09/13/2015 at 12:32 |

|

Another fun fact, there was serious discussion and debate on whether the Cunard liner Queen Elisabeth would better serve the war effort as a troop ship or an aircraft carrier. The decided that if America entered the war they would need the troop ship so she was not converted.

The Powershift in Steve's '12 Ford Focus killed it's TCM (under warranty!)

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

The Powershift in Steve's '12 Ford Focus killed it's TCM (under warranty!)

> No, I don't thank you for the fish at all

09/14/2015 at 09:23 |

|

This is also part of the reason for shifting the island further after. With the island at midship, the elevators are pushed aft or to the port side. Neither location is convenient for moving aircraft between the deck and hangers during launch or recovery. With an aft located island, elevators can be at the center of the ship on the starboard side, which allows them to be used during more or less all phases of flight operations.

You can see the change in design going from the Forrestals

to the later Kittyhawk and Nimitz-class.