"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

10/24/2020 at 20:05 • Filed to: None

6

6

17

17

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

10/24/2020 at 20:05 • Filed to: None |  6 6

|  17 17 |

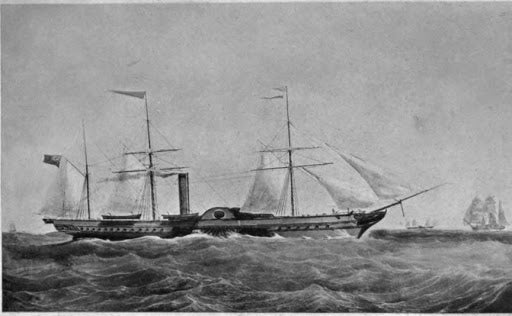

Cunard Line’s Britannia of 1840, built by Robert Duncan & Co., Greenock, Scotland. 1,154 gross tons, 207 ft. long, 115 passengers. service speed 8.5 knots

In 1840, the Cunard Line (founded by

Sir Samuel Cunard, 1

st

Baronet Cunard of Halifax) began

the first regularly scheduled steamship service across the Atlantic,

using a fleet of 4 of the largest, fastest, and most technologically

advanced ships yet built. Although the old fashioned sailing packets

were arguable more comfortable, they took 4 weeks to cross the

Atlantic under the most favorable of conditions, and, subject to the

whims of wind and weather, could take longer than that. Cunard’s

steamships managed the crossing in just 2 weeks, and could do so

reliably all year round, in all weather conditions. In the early

years, Cunard’s only significant competition came from the Great

Western Steamship Company, an offshoot of Great Western Railway,

which struggled to raise the finances necessary to build a big enough

fleet for a regular schedule, but was never really able to do so.

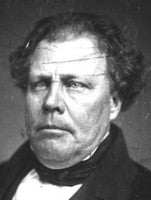

Edward Knight Collins, 1802-1878

In the United States, it wasn’t long

before business leaders and politicians became concerned about the

total dominance of a British firm in rapid, regular commerce between

the two countries and started advocating for a US-based competitor,

which eventually emerged in the form of Cunard’s first serious

competition, the Collins Line.

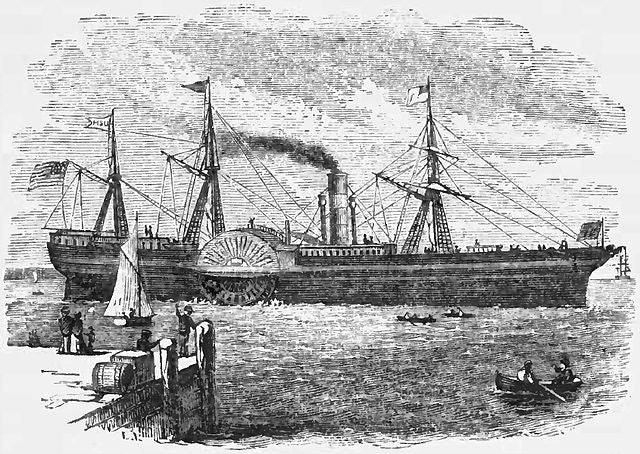

Roscius, flagship of of the I.G. Collins & Son fleet prior to the 1850s

The Collins Line traced its history to

1818, when sea captain Israel Collins decided to go into business for

himself, forming I. G. Collins & Company in New York, with

initially a single secondhand sailing ship used in coastal freight

service along the US East Coast. In 1824, Israel’s son, Edward Knight

Collins, joined the company as a partner, and it became known as I.G.

Collins & Son. During the mid 1820s, the rapidly growing British

textile industry faced a crippling cotton shortage, and I.G. Collins

arranged to charter a fast schooner in early 1825, load it full of

South Carolinian cotton, and sailed it to England, cornering the

market ahead of any rivals. Over the next few years, the company

expanded rapidly, starting regular freight service to the US Gulf

Coast and to Mexico. Israel Collins died in 1831, and Edward took

full control of the company. In 1835, Edward Collins began a regular

transatlantic service, commissioning the largest cargo ship yet

employed on that ocean.

!!!CAPTION ERROR: MAY BE MULTI-LINE OR CONTAIN LINK!!!

!!!CAPTION ERROR: MAY BE MULTI-LINE OR CONTAIN LINK!!!

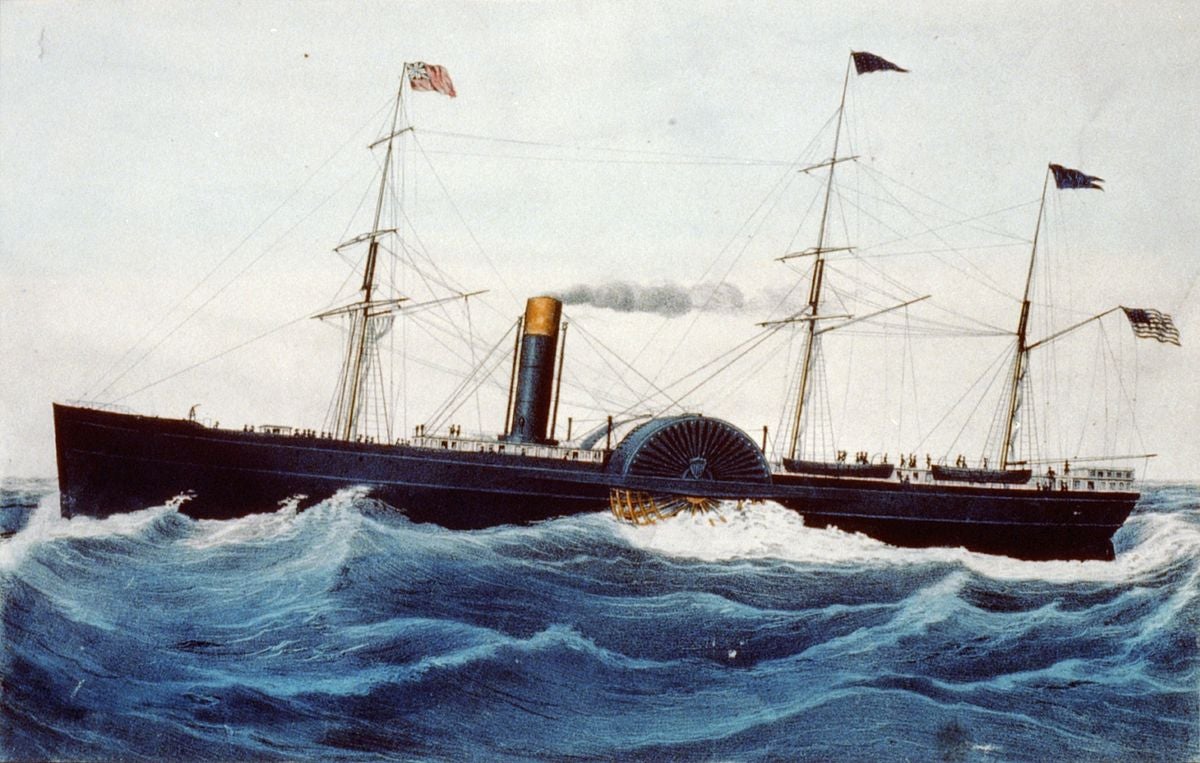

Baltic, delivered November, 1850; 2,723 gross tons, 282 ft. long, sold 1858, scrapped 1880

Pacific, delivered May, 1850; 2,707 gross tons, 281 ft. long, mysteriously lost with all hands, January 1856

Arctic, delivered October, 1850. 2,856 gross tons, 284 ft. long. Sunk September 27, 1854 after collision with Vesta

The US Post Office Department opened

bids for a 10-year contract to carry mail between New York and

Liverpool in 1849, and Collins was already in a prime position to

acquire that contract. Collins proposed a weekly express service on

that route, with a fleet of 5 giant new steamships that would outdo

the best Cunard could offer in every way – larger, faster, and more

luxurious. Unsurprisingly, Collins won the bid, receiving an annual

subsidy of $385,000 through 1860. Due to financial realities, Collins

renegotiated with the Post Office to reduce the planned service to

bi-weekly, with only 4 ships, with the promise to expand the fleet to

5 at a later date. He hired marine architect George Steers, better

known for racing yachts, to translate his specifications into

reality, while the New York shipyards of Brown & Bell were

contracted to build the 4 new liners.

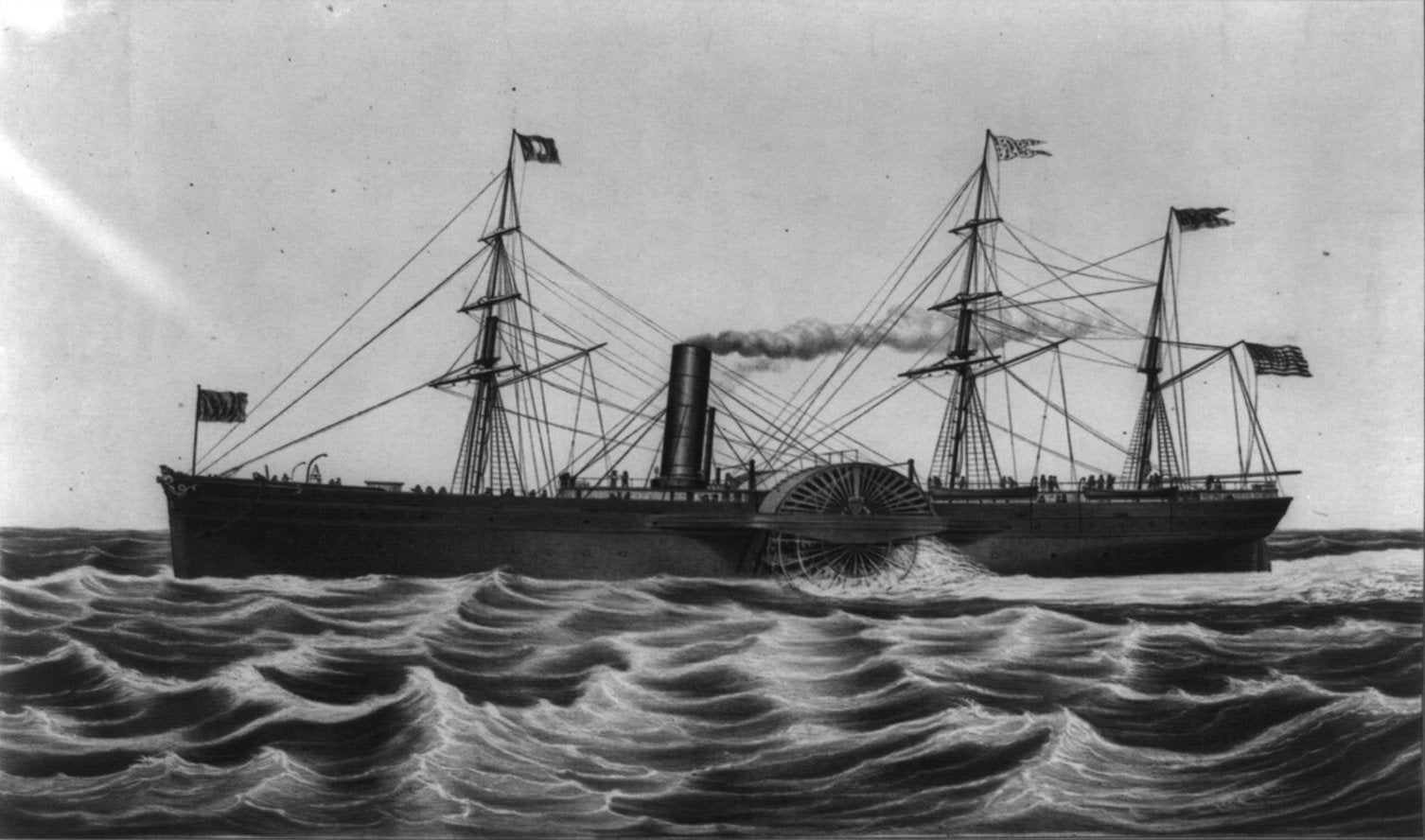

Atlantic, Arctic, Baltic

,

and

Pacific

were delivered between April and October of 1850.

Measuring between 2,707 and 2,856 gross tons and 281-284 ft. long,

they were about twice as large as the biggest ships in the Cunard

fleet, and, with a service speed of 12 knots, were 2 knots faster.

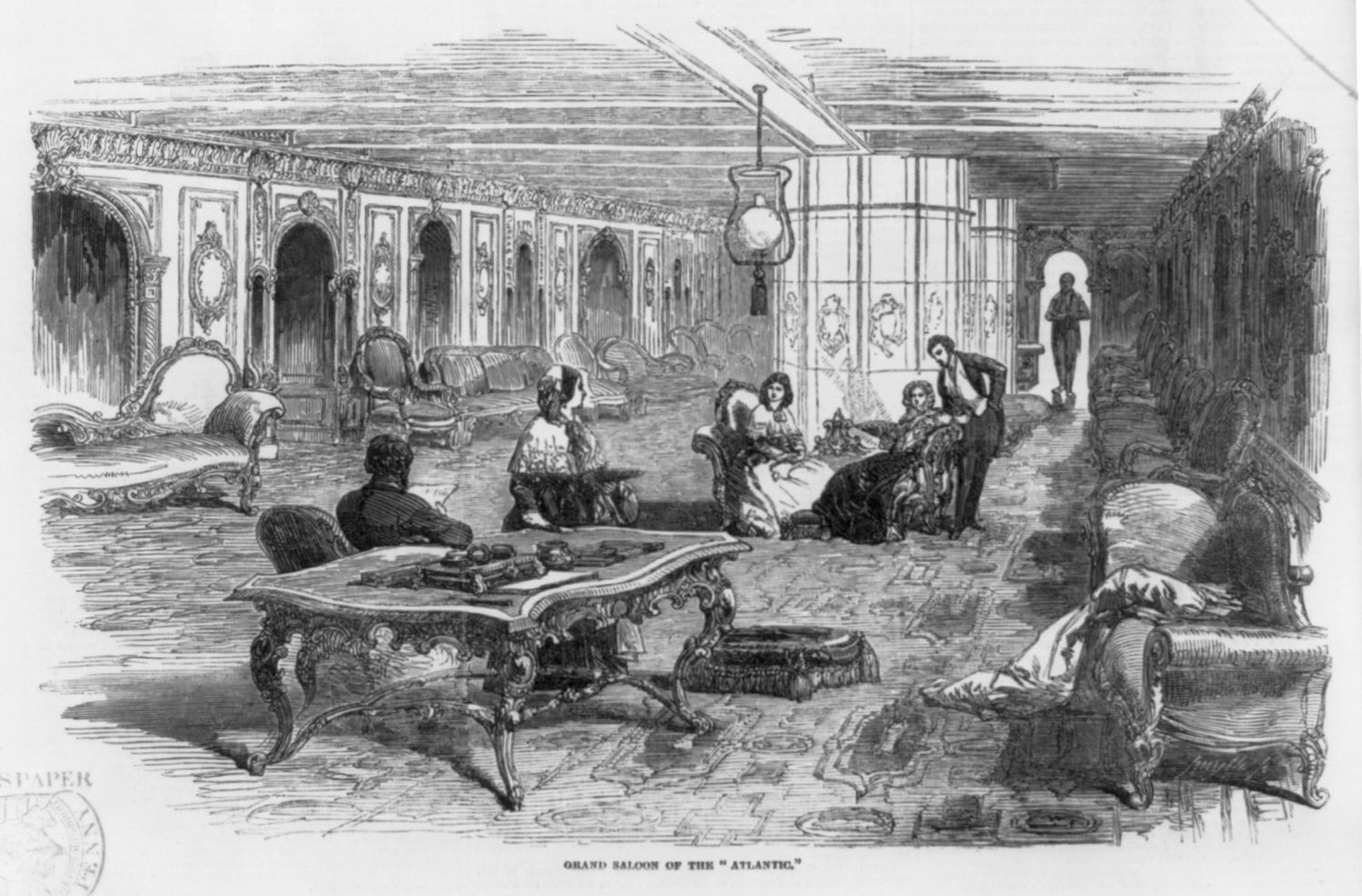

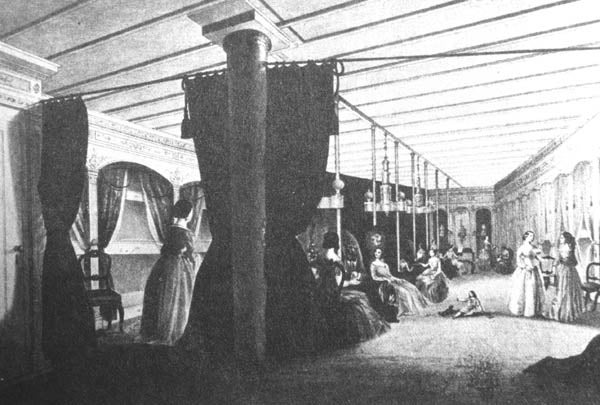

Aside from US Mail and priority express cargo, they also carried 280

passengers – 200 in First Class, and 80 in Second Class. Those

passengers were provided with luxuries previously unknown on the

Atlantic – running water in all cabins, a fresh air ventilation

system and central steam heating throughout, bathrooms (albeit

shared) with hot water and bathtubs, gas lighting, separate lounges

for men and women, and a hair salon.

First Class Ladies’ Lounge on Atlantic

On her maiden voyage in April of 1850, Atlantic set a new record, crossing to Liverpool in 10 days, 16 hours – cutting 12 hours off Cunard’s fastest time.

But, it wasn’t

long before problems set in. Size and luxury came at a price, Collins

had paid $700,000 each for his ships - $2.8 million for the fleet, a

staggering sum for 1850. And, at their maximum speed, Collin’s ships

burned through 87 tons of coal per day, 50 tons more than any Cunard

liner. The company’s commitment to 10 day crossing times meant that

its ships were run flat out all the time, through all weather

conditions, incurring heavy wear and tear to machinery and frequent

storm damage, driving up maintenance and repair costs. At the same

time, Cunard negotiated a new subsidy arrangement with the British

government, raising their support from$725,000 to $836,000. Bigger

and better financed, Cunard doubled their sailing schedules between

1850 and 1852 in an effort to force Collins off the ocean. The

$385,000 federal subsidy, thought sufficient to cover basic operating

expenses in 1849, was suddenly proving inadequate. By 1852, the

Collins Line was hemorrhaging money and had been forced to liquidate

its fleet of sailing ships and put all resources into the

transatlantic steamship service. Putting extra pressure on the

situation, in 1853, US Congress voted to require that Collins double

his service schedule during the dead of winter, in order to directly

match Cunard’s frequencies. Collins insisted that they needed extra

financial support to avoid bankruptcy, requesting an increase to

$858,000. A new agreement was reached during 1854 – Collins would

receive the bigger subsidy, but the Post Office would have the right

to cancel the agreement at any time with only 6 months’ notice. A

crisis seemed to have been averted, the Collins Line remained

solvent, but a bigger, and more real disaster was about to strike.

Wreck of the Arctic

On April 27, 1854,

Arctic

left New York bound for Liverpool with 233 passengers –

among them Edward Collins’ wife and two children. In thick fog 60

miles off the coast of Newfoundland, the speeding Arctic collided

with the iron hulled French freighter

Vesta

. Her captain made

an effort at reaching shore, but

Arctic

sank just 15 miles

from the coast with the loss of 322 passengers and crew out of the

374 on board, including Collins’ family.

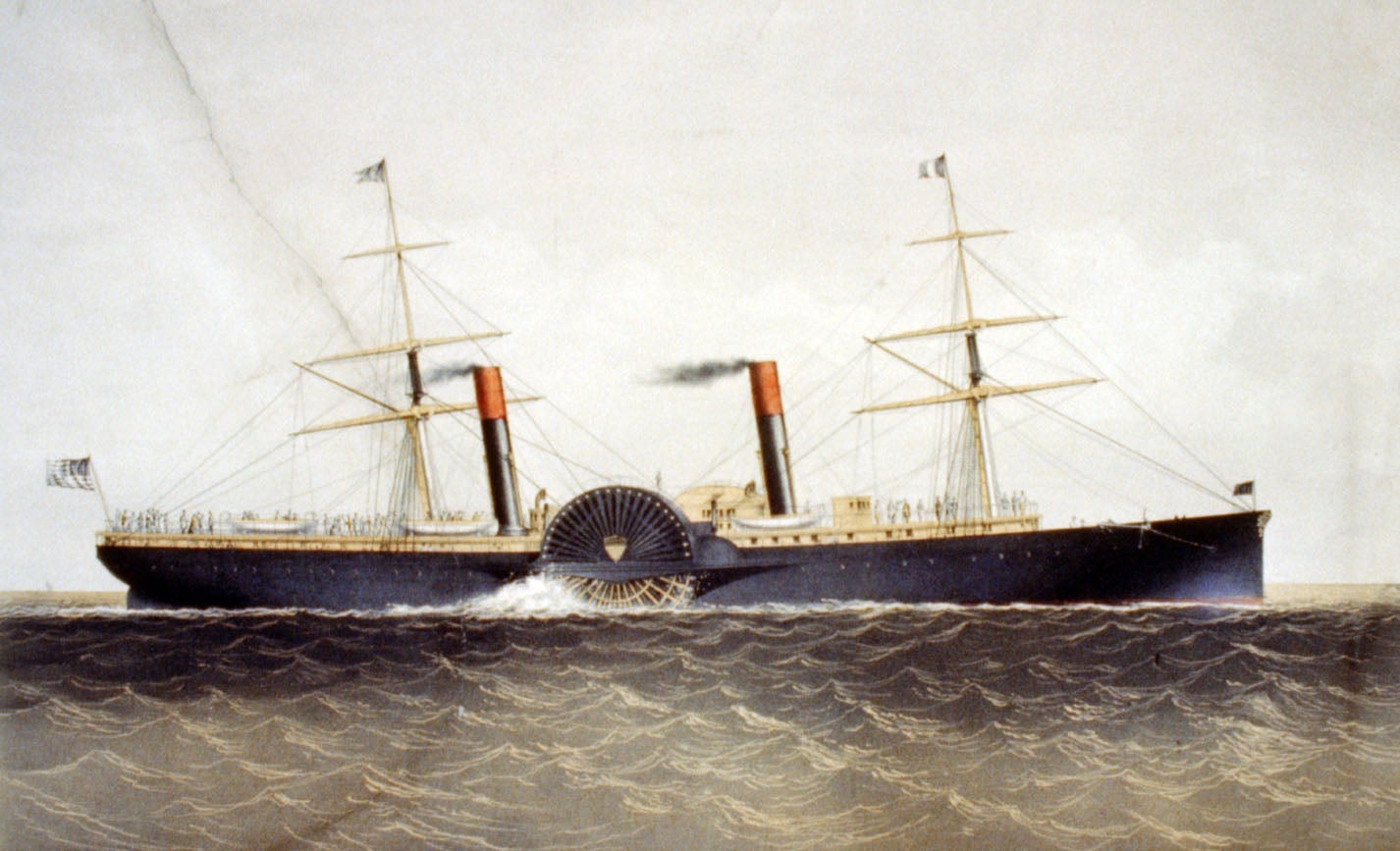

The new Adriatic, 3,670 gross tons, 355 ft. long. Sold at auction 1859, scrapped sometime before 1890.

Grief stricken, but undeterred, Edward Collins vowed to rebuild, ordering an even bigger, faster, and more luxurious replacement – the Adriatic – for delivery in 1856, though, due to mechanical problems discovered on sea trials, Adriatic ’s entry into service would be postponed to 1857. In the meantime, disaster struck again when the Pacific mysteriously disappeared without a trace in January, 1856, outbound from Liverpool with 45 passengers and 141 crew. Her captain had been under pressure to beat Cunard’s new Persia into New York, and the conventional assumption is that she must have hit an iceberg somewhere en route.

With 2 of the company’s 4 ships lost, their new flagship delayed with technical problems, and the economy heading into a recession, the Post Office cut Collins’ operating subsidy from $858,000 back down to $385,000, effective August 1857. The company stumbled along for a few more months, but ran out of cash and suspended services in February, 1858, and their assets were liquidated in bankruptcy in April of 1858.

Edward Collins managed to hold onto some personal assets, remarried, and invested in coal and railroad businesses, dying in New York in 1878. It would be several decades before another American company made any serious attempt to challenge Britain’s dominance in transatlantic shipping.

Just Jeepin'

> ranwhenparked

Just Jeepin'

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 20:46 |

|

You should adjust the time stamp on your posts; because this one is listed as 40 minutes old, it’s not at the top of the page, so I almost missed it.

ranwhenparked

> Just Jeepin'

ranwhenparked

> Just Jeepin'

10/24/2020 at 20:50 |

|

I guess, I’ve never messed with that feature

DipodomysDeserti

> ranwhenparked

DipodomysDeserti

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 20:53 |

|

If you put all these together and publish them, I’d buy a copy.

My great grandfather worked in the boiler room of a Destroyer during WWI. Left from NYC and arrived back in SF. Had a camera with him when they stopped in France at the end of the war and snapped a shot of Woodrow Wilson. It would be cool to read about some warships.

Just Jeepin'

> ranwhenparked

Just Jeepin'

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 20:54 |

|

I get burnt by that a lot when creating hour rule posts. Several minutes afterwards one or two posts will show up behind mine in the timeline and it l ooks like I can’t count to 60 minutes.

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 21:22 |

|

Just before you post, click “reset” on the time to make it current.

Just Jeepin'

> ttyymmnn

Just Jeepin'

> ttyymmnn

10/24/2020 at 21:24 |

|

Whoa, wait, what? I had no idea.

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 21:26 |

|

Very interesting read. Thanks for putting this together. Interesting how big a role government subsidies can play in industry competition (cough cough Airbus).

On April 27, 1854, Arctic left New York bound for Liverpool with 233 passengers – among them Edward Collins’ wife and two children. In thick fog 60 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, the speeding Arctic collided with the iron hulled French freighter Vesta . Her captain made an effort at reaching shore, but Arctic sank just 15 miles from the coast with the loss of 322 passengers and crew out of the 374 on board , including Collins’ family.

Unless I’m misreading this, something doesn’t quite add up.

ttyymmnn

> Just Jeepin'

ttyymmnn

> Just Jeepin'

10/24/2020 at 21:28 |

|

Yup. That way, when you spend an hour writing something, it doesn’t end up half way down the page. It’s really pretty dumb of Kinja to do it that way. It should post immediately regardless of what time you started writing the post.

Just Jeepin'

> ttyymmnn

Just Jeepin'

> ttyymmnn

10/24/2020 at 21:29 |

|

Agreed. Thanks for the reset trick; I had seen it there all along, but eventually my mind started ignoring it automatically since I didn’t know w hat it did.

Aremmes

> ttyymmnn

Aremmes

> ttyymmnn

10/24/2020 at 21:41 |

|

374 persons minus

233 passengers equals 141 crew.

ttyymmnn

> Aremmes

ttyymmnn

> Aremmes

10/24/2020 at 21:48 |

|

I think I understand it now, but I guess it could have been a little clear. Arctic had 374 souls on board which included 233 passengers. When it sank, there were only 52 survivors. If my math is right, and it may not be...

Goggles Pizzano

> ranwhenparked

Goggles Pizzano

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 21:53 |

|

This is great Oppo.

ranwhenparked

> ttyymmnn

ranwhenparked

> ttyymmnn

10/24/2020 at 22:09 |

|

Yes, that’s right - 233 passengers, 141 crew, 374 total on board, 52 survivors.

Basically all railroads, passenger shipping lines, and airlines from the 19th and 20th centuries ow

ed pretty much their entire existence to government subsidies, which do continue in various ways today with frequent

bailouts and nationalizations of airlines around the world.

Goggles Pizzano

> ranwhenparked

Goggles Pizzano

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 22:10 |

|

If it were I that put the time and effort into writting this I’d change the posted time, even now.

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 22:12 |

|

So folks like Cornelius Vanderbilt got filthy rich mainly through government contracts and subsidies?

ranwhenparked

> ttyymmnn

ranwhenparked

> ttyymmnn

10/24/2020 at 22:14 |

|

Maybe not his first few million, but most of

his subsequent millions, yes.

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

ttyymmnn

> ranwhenparked

10/24/2020 at 22:15 |

|

Thanks again for the article. I enjoyed it.