"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

12/09/2015 at 18:49 • Filed to: Porsche

0

0

8

8

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

"davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com" (davesaddiction)

12/09/2015 at 18:49 • Filed to: Porsche |  0 0

|  8 8 |

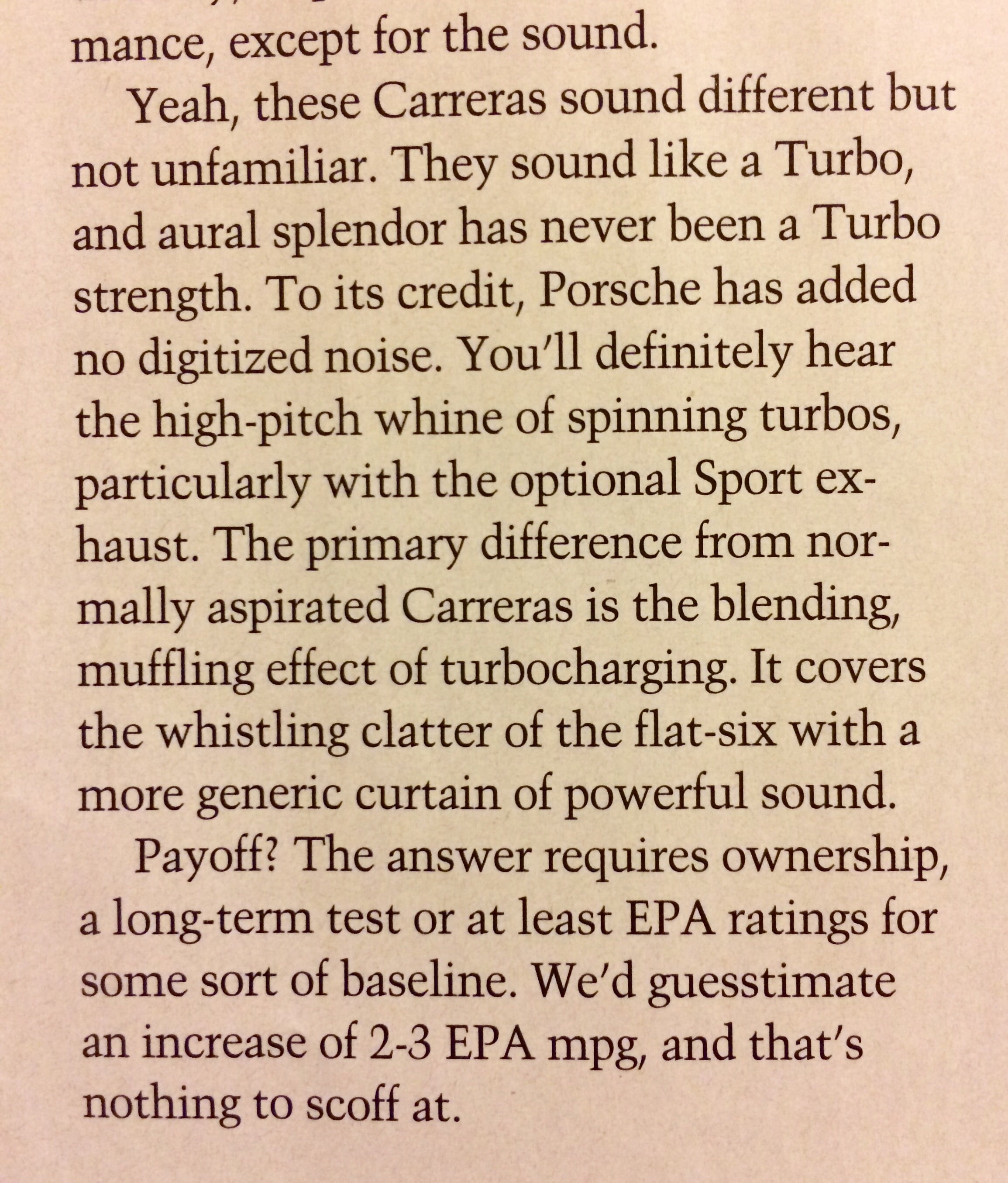

But their hands were tied, it seems. At least they didn’t fake the noise in-cabin, like so many others.

RallyWrench

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

RallyWrench

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

12/09/2015 at 19:00 |

|

Haha, I just read that in AW at lunch today and had a similar reaction. Depends on one’s definition of “aural splendor.”

willkinton247

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

willkinton247

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

12/09/2015 at 19:00 |

|

I also read this Autoweek. Haha

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> willkinton247

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> willkinton247

12/09/2015 at 20:01 |

|

Well, there's at least three of us!

Master Cylinder

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

Master Cylinder

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

12/09/2015 at 20:13 |

|

That NA boxer 6 sounds glorious. I shall scoff at anything that dampens that sound.

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> RallyWrench

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> RallyWrench

12/09/2015 at 20:32 |

|

Turbos inherently lessen the ability of the sound engineers to create a pleasing sound. Listened to a M engineer admitting this in a video about the new M3/4.

RallyWrench

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

RallyWrench

> davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

12/09/2015 at 20:43 |

|

That’s true, but it depends on one’s definition of pleasing. I love the sound of many turbo engines, especially that of the 930, and I think the new F1 cars sound fine. Obviously I’m in the minority on that.

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> RallyWrench

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> RallyWrench

12/09/2015 at 21:00 |

|

Yeah, everyone’s different, for sure. Having heard both the old F1 V8s and the new turbo 6s live, I much pretty the screaming fury of the former. Here’s a clip of the interview:

What characterises the sound of a naturally aspirated engine as employed until now in the recently superseded BMW M3?

A naturally aspirated engine has relatively unobstructed lines both from the air intake and to the exhaust systems. A small proportion of the sound that the driver perceives as an acoustic indication of the engine load level in the interior of the vehicle comes from the direct transmission of structure-borne engine noise, while the majority of the noise is transmitted through the air directly from the intake tract; however the noise level is damped to an extent by a combination of the long intake distance and the air filters. In the case of a naturally aspirated engine, this damping can be decreased further by fitting a larger valve to the air box, thus acoustically dethrottling the air intake – as is the case in the BMW M3 CSL for instance. The resulting acoustic effect is very positive.

The situation is similar on the exhaust side of the engine. Only the length of the exhaust tract and the silencers reduce the combustion noise emanating from the engine.

A naturally aspirated engine offers a very broad-banded frequency spectrum, which is useful when it comes to developing acoustic characteristics. A large engine speed range combined with many cylinders and a large engine size have a further positive impact on the available fundamental sound spectrum.

What is it that distinguishes the sound of a turbo engine from that of a naturally aspirated design? And why is this so?

The acoustic properties of a turbo engine represents a great challenge to sound designers.

The turbo charger’s paddle wheels that are located in the air intake and exhaust tracts are effectively a barrier that blocks off intake and combustion noise.

As a result, the airborne noise transmitted from the intake is virtually eliminated. And this is immediately noticeable in the interior of the vehicle. Only the relatively weak structure-borne sound transmission remains intact.

The situation is similar on the exhaust side: all combustion gases that flow through the exhaust turbine are subjected to extremely high acoustic damping. Only those exhaust gas flows that are not needed for the turbo charger and which pass through the waste gate past the charger produce a combustion sound that can be utilised. However, these are precisely the acoustically relevant exhaust gas streams that are reduced still further to facilitate the outstanding response characteristics of the M TwinPower Turbo inline six-cylinder engine of the new BMW M3 and BMW M4.

This all sounds somewhat complicated...

Maybe the following example will make it all a bit clearer:

If you imagine a hall (the space beneath the bonnet) in which an orchestra of many different instruments (the engine) is playing. Some of the instruments are able to produce both low and high sounds, i.e. they have a uniformly good bandwidth or a broad sound spectrum.

However, alongside this hall is another, separate hall (the passenger *******, which is joined to the first hall through different sized doors (the body, the air intake tract and the exhaust system). In the case of a naturally aspirated engine, most or at least many of these doors are open, which means that the driver in the room next door can still hear a large frequency band of the sounds produced.

However, in the case of a turbo engine, it is as if the majority of these doors were closed. You can hear something – maybe the basic character of the music as it plays (the combustion) – but the audible portion is restricted to the low-frequency range. A large section of the acoustic frequency spectrum is lost through the turbo system.

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> Master Cylinder

davesaddiction @ opposite-lock.com

> Master Cylinder

12/09/2015 at 21:04 |

|

Yeah, when I buy my first Porsche, it will be an NA 6 with good-old hydraulic steering and three pedals.