"Jonee" (Jonee)

"Jonee" (Jonee)

11/13/2014 at 14:12 • Filed to: Rovin, microcars, cyclecars, France

4

4

4

4

"Jonee" (Jonee)

"Jonee" (Jonee)

11/13/2014 at 14:12 • Filed to: Rovin, microcars, cyclecars, France |  4 4

|  4 4 |

All sorts of characters started microcar companies in the first half of the 20th Century. From clever, self-taught engineers like !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! who built little masterpieces out of battlefield scraps; to men like !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , heir to a stocking empire who had no engineering skills whatsoever and whose cars were barely roadworthy. Raoul Pégulu was the Marquis de Rovin, actual royalty, and he and his little brother Robert built some of the fastest and handsomest micro machines in the world.

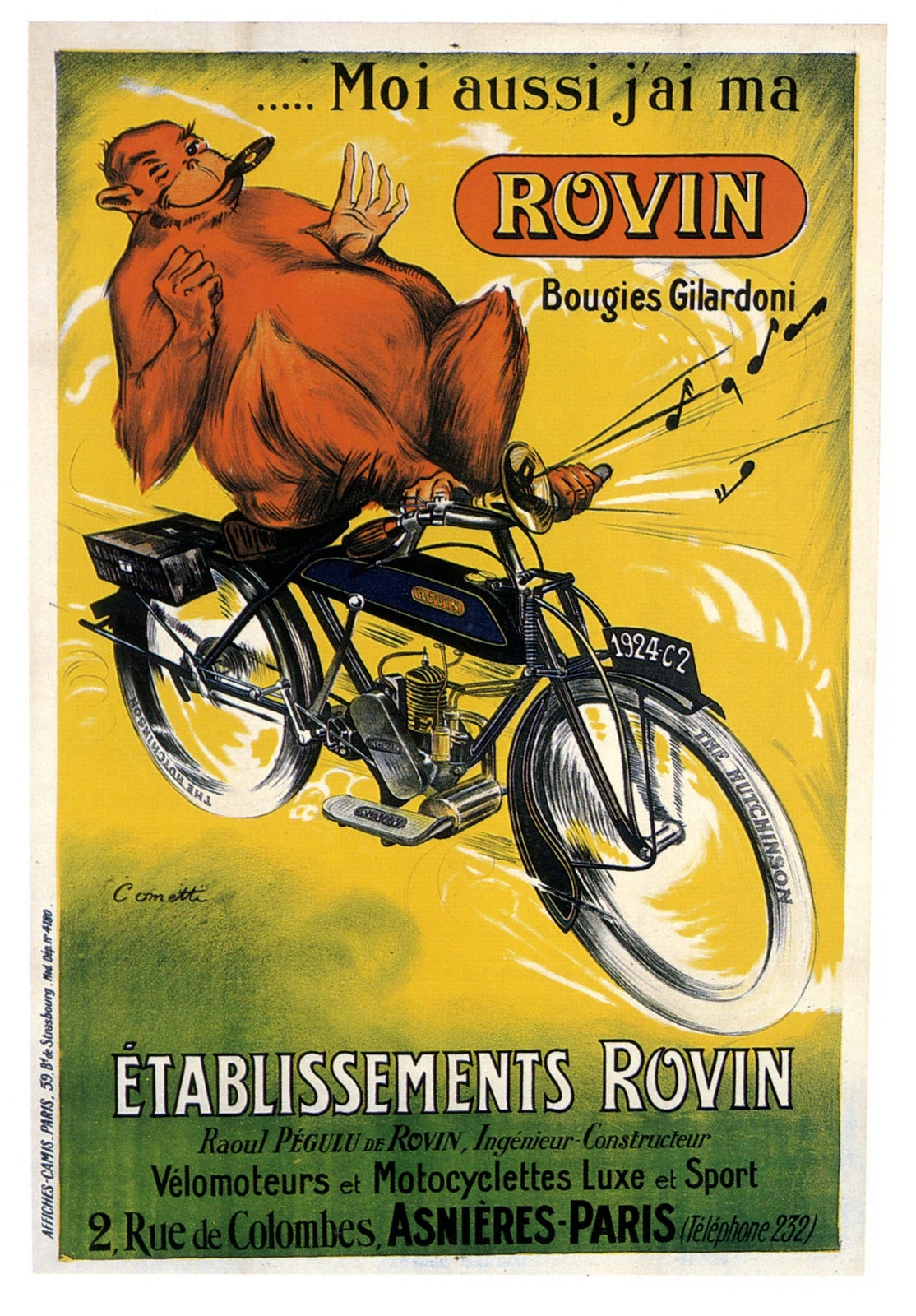

Raoul was born in Spain in 1896, but owing to his status, went to school in Paris. He was 18 when the First World War started and was quick to enlist. Raoul was the oldest son in a family of 8 children, but still too young to die according to his parents who tried in vain to get Raoul to return to Spain. But, the war was seen as an adventure to young men in those days and the Marquis seems like he was something of a daredevil. Before long, he was in the trenches at the front. He spent several years as a soldier until he was seriously wounded for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. WWI was the first time motorcycles were in widespread use and Raoul, who loved excitement, became enamored with them. He stayed in Paris after the war and, in 1921, opened his own cycle shop in Colombes on the outskirts of the city. He was soon joined by Robert and the two of them focused on building light bikes with small displacement motors.

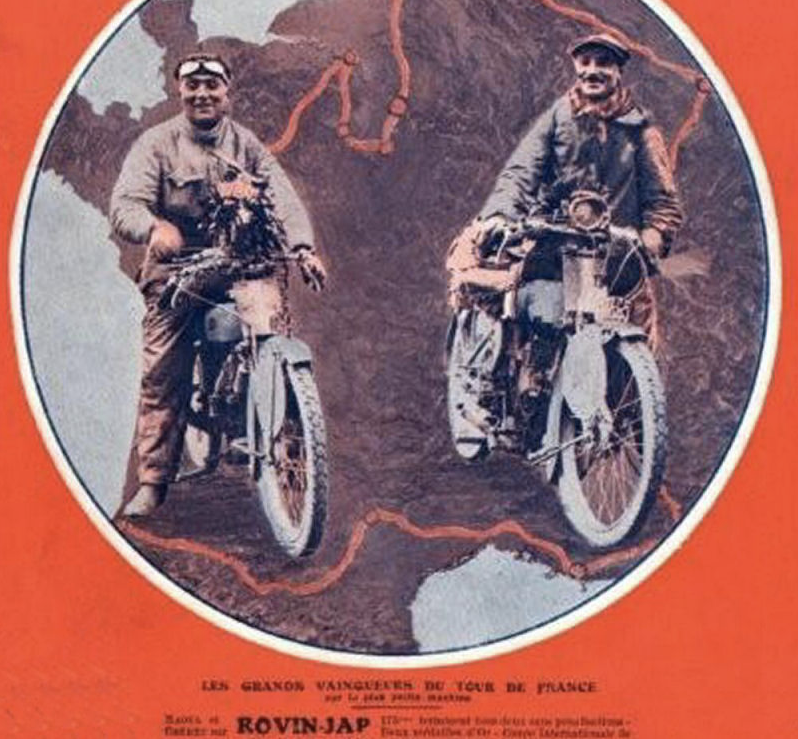

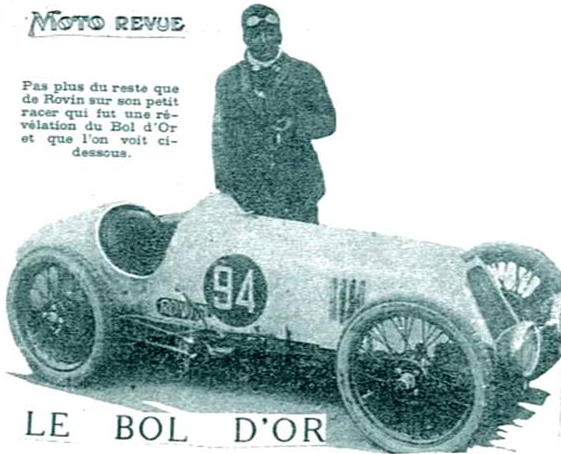

Resources were still tight because of the war and bikes with 75cc up to 175cc engines were popular. The Rovins formed their own racing team and pretty much dominated the cylindrées petites category. And, I mean dominate. At one 100KM race in 1923 that had been broken up into a series of elimination races, a Rovin won one by 15 minutes and another by 17 averaging over 70kph and setting world records along the way. Rovins broke 15 world records and racked up victories all over the continent. They were especially successful in endurance races winning the 24 hour Bol D'Or 8 times in their classes, and the Tour de France for motorcycles 7 times.

Raoul himself rode one of his bikes to victory in the 1923 Grand Prix de France's 175cc class, and finished well in many other races. Their bikes used motors made by French companies like Train, JAP, Velocette, and MAG, but also engines of Rovin's own design. One of these was a screaming 98cc single cylinder two-stroke with two carbs that put out 4 horsepower meaning 41HP/liter with no supercharger. Their motors were technical marvels and some featured overhead, and others side valves. They didn't just race their bikes, they sold them as well and Rovins were pretty popular due to their racing success. They were even exported, selling well in Spain where they also set records.

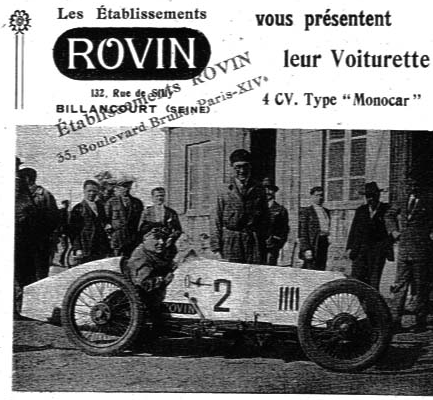

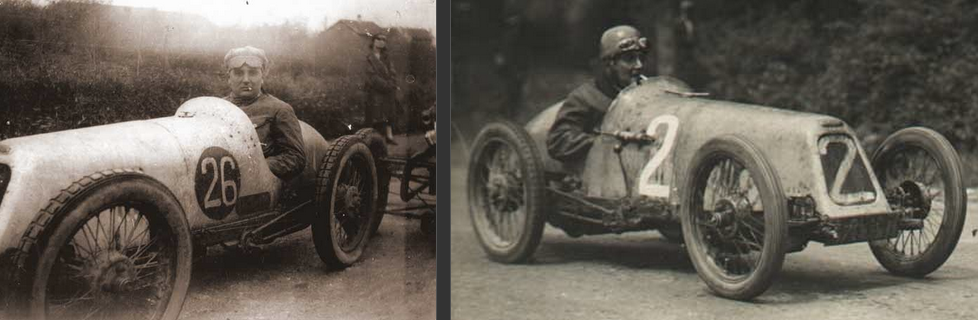

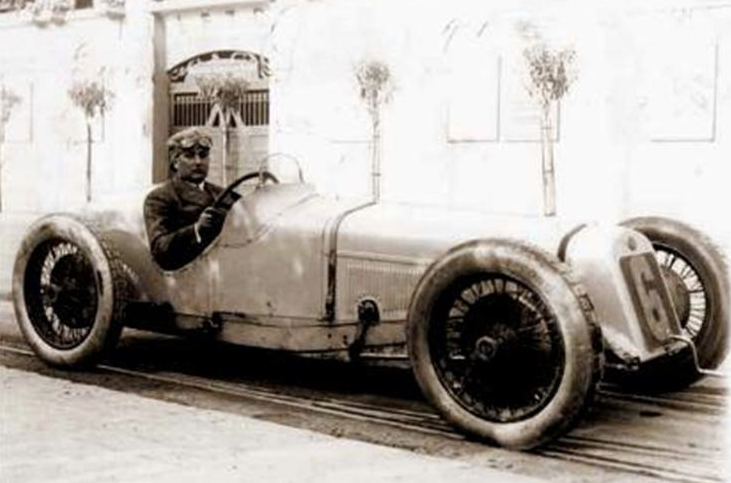

The mid-twenties was the time of the cyclecar boom in France. Cyclecars were what they sound like, minute cars built around motorcycle frames powered by small, usually air-cooled engines and chain drive. They started racing on the same circuits as motorcycles and it wasn't long before Raoul entered the fray.

He began with teeny tiny little things with 100cc and 175cc motors, then he scaled them up ever so slightly. He had started building bigger 500cc motorcycles and, at the 1926 Paris Auto Salon, he debuted the Rovin Monocar, a cyclecar with a 498cc JAP engine.

The little car became a success both on the race course and the sales floor. Both Raoul and Robert raced in Rovin cyclecars and they became as accomplished as the motorcycles. Raoul even became the only person to ever enter the Bol D'Or in both the motorcycle and cyclecar races which were run back to back. In those days a single rider or driver did the whole 24 hours all by himself which meant Raoul was going full throttle in some machine for 48 hours with just 4 hours of breaks. Yikes!

Raoul became a pretty renowned racecar driver in his day. In '27 he set 4 cyclecar records, and the following year had his most spectacular win at Château-Thierry in a car that had had its body panels removed because Raoul was sick of squeezing in and out of it.

By this time the brothers had grown passionate about bigger sports cars, and Raoul began driving a Delage 15 s8 which he entered in the very first Monaco Grand Prix. He had to retire after the 82nd lap because he had burned his hand on the shift knob. Used to driving 3-speed cyclecars, he apparently was only using the first two of five gears and the transmission was volcano level hot to the point that he needed medical attention.

He also drove an American Nash in the Tour de France auto race in 1930 which doesn't sound very sporty, but it did have the biggest engine he had yet driven. As the thirties dawned, the Rovins opened a sports car dealership on the Boulevard Pereire in Paris and branched out into building three-wheeled utility vehicles. Their interest in small bikes and cyclecars waned as Raoul had now discovered flying and began racing planes. This guy just couldn't sit still and kept putting himself in faster and faster vehicles. He raced this Renault-engined Potez in the 1931 Tour de France for planes if you can believe there was such a thing.

I'm surprised there wasn't a Tour de France for riding mowers, but if there had been, Raoul would have entered it. In 1932 the Rovins closed their factory to focus solely on the much more lucrative dealership until Hitler came along.

By the time WWII started, the brothers had also opened their own auto design studio. During Nazi occupation, automobile production was outlawed (the closest thing to a new car one could buy was a pedal-powered !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! ), but that didn't stop people like the Rovins from continuing their design efforts in secret. Like a bunch of others, Raoul and Robert remembered the last war and anticipated the need for cheap cars when the war ended. And, they became one of the first out of the gate. In August of 1945 they already had a sketch for their "Type D" published in Automobilia magazine which means there was probably an A, B, and C penned while the war was still on. They constructed and tested a monocoque two-seat prototype with fully independent suspension powered by a Rovin air-cooled 260cc four-stroke motor the following year. Soon after, they built a show version with a newly styled body, and had two "D-1's" on display at the Paris Salon in October 1946.

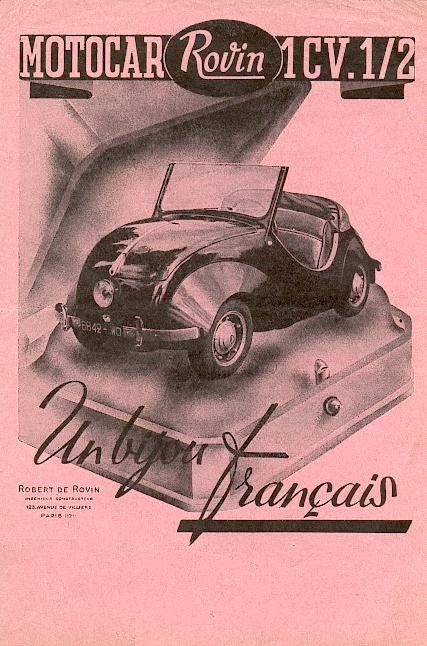

It was tiny and adorable with swooping lines looking like the fanciest of pedal cars. Those curves were meant to keep manufacturing costs down since they could be made without the need of stamping presses, and the low sides meant no doors necessary. There were a few other similar microcars on display, but the Rovin was probably the prettiest and most refined, and was well received by the press and public. In 1947 the brothers bought shares in Delaunay-Belleville so as to use their plant in St. Denis where luxury cars and military trucks had been made. They began making improvements on the D-1 to ready it for production.

It got a "beams and backbone" Y chassis that was similar to a Tatra or Renault Alpine, and a 423cc flat twin water-cooled side valve engine that put out 10 horsepower sat between the tines. It was a proper car engine unlike the two-stroke scooter motors in most microcars, and its small displacement kept it in the 2CV tax bracket, a key selling point. Suspension was still all independent with transverse leaf springs in front and coil springs in back. The rear wheels were chain driven by a three-speed gearbox/differential.

The body was lengthened slightly and it grew a second headlight. It only weighed 660 lbs. which meant it could get up to 50 mph which must have felt pretty quick. The "D-2" made its debut at the 1947 Salon and production launched.

At 150,000 Francs, it was more expensive than a Citroen 2CV even though it was much smaller, but it was actually more powerful and had beaten it to market.

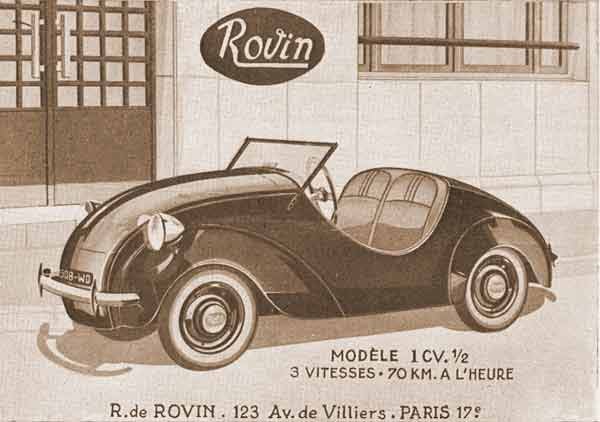

It seems that around this time Raoul became ill and Robert took full control of the company. Raoul died in 1949 and I'm not sure what killed him, unfortunately. By the time of his death less than 700 D-2's had been sold, not a bad figure for a company built from war remnants, but it wasn't great, either. Their cars were almost over engineered for what they were and didn't produce much profit. Citroens and Renault 4CVs were now on sale and, although the Rovin was comparable performance-wise, those cars were more like real cars. The only catch was there was a waiting list for them and Rovin could deliver you a car immediately. So, Robert produced an all new, more modern looking body and called it the D-3.

I think it's a strikingly beautiful simple and clean design. Totally symmetrical to make production cheap and easy with gently curving corners, it's got an elegance unmatched in any other micro. The only thing that might spoil it are the bugeyes, but I think they're charming. Robert apparently thought it should only be painted black, but I like this white one.

The mechanicals were unchanged from the D-2 and the addition of doors added weight bringing performance down. But, it was comfortable and meant for cruising the boulevard, not drag racing. Of course, that didn't stop someone from rallying one at Monte Carlo in 1950.

Price jumped to 200,000 Francs making it one of the more expensive microcars in France. Sales were steady at first and Rovin began exporting cars. Around 52 were sent to the Netherlands where, due to low import duties because of its size, it was the cheapest car on sale. That still didn't stop it from taking 3 years for those cars to sell by which time Citroens had made their way there spelling the end for Dutch Rovins. One place Rovins proved surprisingly popular was South America, incredibly enough. Several hundred found their way there even making it to Paraguay of all places. Around 800 D-3's were built and sold, more than the D-2, but still not exactly like hotcakes. So, in 1951 Robert made more improvements in hopes of boosting sales.

The new D-4 got a slightly larger 462cc, 13 horsepower engine and eventually a 4th gear. Price was up to 279,000 Francs, but for 250,000 you could still get one with the smaller engine. The headlights were also integrated into the fenders at one point which looks pretty sharp and modern for the time.

None of this ended up helping any. 387 Rovins sold in 1951 compared to 395 the year before. By the early 50's, production of Renaults and Citroens was ramping up so the waiting list was no more. The Beetle was also making inroads and the French economy was improving, so sales of Rovins dropped to 110 cars in 1953. After selling only 20 the following year, Robert de Rovin retreated from the car business for all intents and purposes. The old Delaunay-Belleville factory was sold off. Robert did still offer the cars on a special order basis until 1961, making Rovin the longest lasting postwar French microcar marque. However, only a few were made in the second half of the 50's and total Rovin production was less than 3,000 cars. Parts were available 'til the end to keep the existing Rovins on the road and they do have a decent survival rate. Like his brother, Robert then got into airplanes, and Rovin the company began doing aviation related work until when, I'm not sure. The de Rovin brothers are largely forgotten today, but they were important figures in the history of French motor vehicles. They may not have had the longevity of Renault, or the prestige of, say, Talbot-Lago, but everything with the Rovin name was simple, stylish, well built, and impeccably engineered. Most importantly, even though they were descended from royalty, their products were always meant for the masses during times when cheap transportation was desperately needed. Rovins have always been considered little gems in the microcar world and now demand upwards of $50,000 for a nicely restored one which I'm sure would delight Raoul.

Many thanks to !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! and Peter Svilans for their help researching this one.

Jobjoris

> Jonee

Jobjoris

> Jonee

11/14/2014 at 05:44 |

|

Great write-up, epic story! That top-pictured D4 is the one on display in the Louwman Museum in The Hague permanently, that one is immaculate!

Jonee

> Jobjoris

Jonee

> Jobjoris

11/14/2014 at 12:21 |

|

I knew you'd recognize that one.

Jobjoris

> Jonee

Jobjoris

> Jonee

11/14/2014 at 16:04 |

|

Well, you'll probably recognize my 'French Friday' post on Live and Let Diecast next week as I'm putting up a French microcar on stage ;-)

Jonee

> Jobjoris

Jonee

> Jobjoris

11/14/2014 at 16:20 |

|

Cool, I look forward to it. I really dug today's Alpine entry. As I mentioned, there's a Rovin connection to those cars. I realize I've been missing your French Fridays, so I'm going to go catch up.