"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

10/04/2014 at 19:47 • Filed to: Shiplopnik

6

6

3

3

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

"ranwhenparked" (ranwhenparked)

10/04/2014 at 19:47 • Filed to: Shiplopnik |  6 6

|  3 3 |

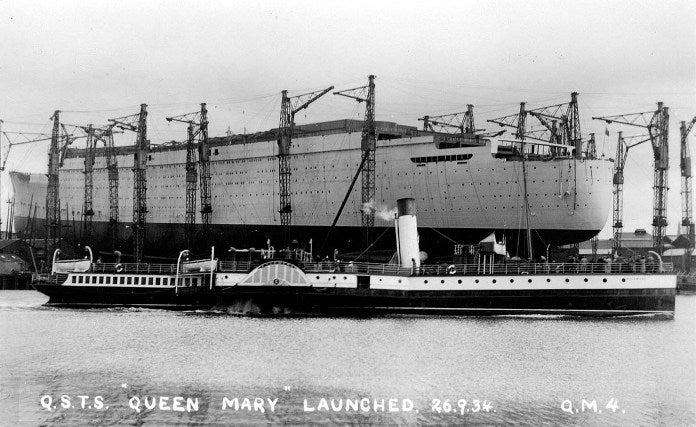

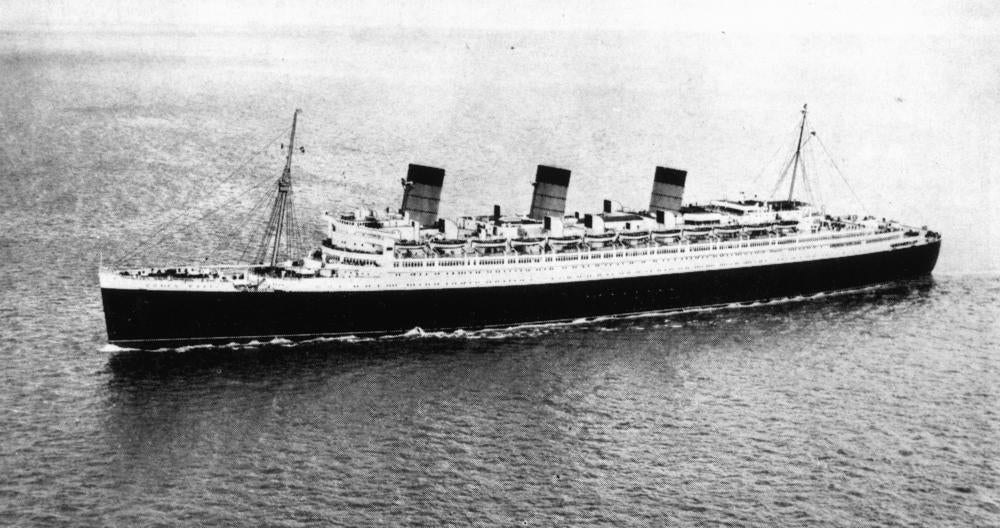

As The 80 th Anniversary of the Queen Mary 's christening and launch on September 27 th 1934 has come and gone, I've found myself reflecting on what's become of the ship in the years since arriving in Long Beach, California in 1967 and what is left of it today. When the Queen Mary was completed in 1936, ocean liners were important national symbols, the ship was a symbol of Britain's resilience in the face of the Great Depression and was intended to be a floating showpiece, demonstrating to the world the best that British industry, technology, and craftsmanship could accomplish. She was the fastest and largest ship ever built at the time (though the French Line's Normandie would retake the latter title a year later thanks to the addition of a carefully sized deckhouse) and remains one of the most famous ships ever built. In the 1930s, everything the Queen Mary did was noteworthy – breaking a new speed record, heading into drydock for maintenance, the appointment of a new captain, the visit of a member of the royal family, etc. would all get reported in magazines, newspapers, and newsreels. Almost every detail of the ship was considered worthy of publication.

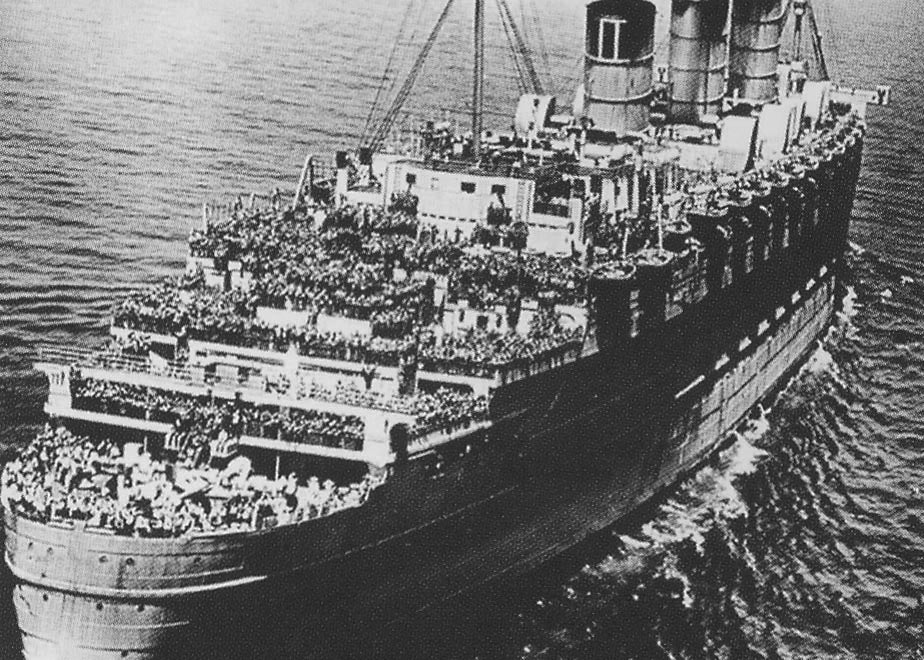

During WWII, the ship distinguished itself as a crucial part of Allied logistics, converted to carry 15,000 troops at a time, Winston Churchill estimated that the transport capabilities of the Queen Mary and her running mate Queen Elizabeth was enough to have shortened the war in Europe by a full year. The ship was so fast that it sailed without any protective escorts, as it could outrun all naval vessels then in service and it was considered more dangerous to slow down and stay with a convoy. Hitler offered a generous cash reward for any U-boat captain that could sink her, and she acquired the nickname of the "Grey Ghost" because of her ability to seemingly appear and disappear almost instantly.

After the war, the Queen Mary settled back into her civilian role as a transatlantic liner and was one of the most popular ships of the 1940s and '50s, with routinely high occupancy rates. But, all good things come to an end, and when the first jet airliners started crossing the Atlantic in 1958, that end approached rapidly. By the mid 1960s, passenger numbers had collapsed and the giant Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were often nearly empty on many sailings, especially in off-peak seasons. In 1966, Cunard Line announced the ship would be withdrawn from service after the following summer and sold by sealed bid auction to the highest bidder, with the provision that the ship not be used in any way that directly competed with Cunard's remaining services.

Enter Long Beach. Due to decades of poor city planning, the once vibrant waterfront, known as the Pike district, had become a depressed slum by the 1960s. The Los Angeles River flood control project and construction of a new cargo terminal destroyed the beaches that gave the city its name, businesses fled, the amusement park closed, and the tourists went elsewhere. Revitalizing the Pike was considered a top priority, and the city council voted to appropriate some of the city's Tidelands funding to the effort, approving money for the construction of a hotel, convention center, shopping center, and maritime museum on the waterfront. It was hoped that those attractions would lure visitors back to the area, even without beaches. But, before the construction project could get off the ground, Cunard announced that the Queen Mary was up for sale and rumors started circulating that New York, San Francisco, and a few other large cities were planning to place bids to acquire the ship as a static attraction. Someone on the Long Beach city council suggested that they use the Tidelands funds appropriated for waterfront redevelopment to acquire the ship instead. It was argued that the Queen Mary was big enough to contain all the necessary components – hotel, museum, convention center, and shopping center – within it, saving time and money over construction of new buildings on land. Also, the Queen Mary 's status as a world-famous icon would instantly put the city and the project on the map, as it were, basically doing all the marketing and publicity work for them. Long Beach could buy two world-class attractions for the price of one. The idea was accepted, the bid submitted, and Long Beach amazingly outbid all of its larger and better financed competitors to become the proud owner of an ocean liner. The Queen Mary sailed into Long Beach harbor in November 1967 and has been there ever since.

And, that's were it all sort of went wrong. Long Beach bought the ship for its name recognition and status as a world-renowned icon, not because they were at all interested in saving or preserving the vessel as an important architectural and engineering artifact. Basically, all of the interiors were considered expendable, to be gutted, rebuilt, and reconfigured as needed to suit its new roles.

Today, people look at how much of the ship has been gutted and shake their heads at the destruction, but in 1967, it made perfect sense. To understand the reasons behind the conversion, it's important to remember a few things:

1. Although the Queen Mary is today one of only 2 early 20 th century ocean liners remaining in the world, in 1967, it wasn't that unique. There were still a number of ocean liners in service on the Atlantic and other routes around the world (including the Queen Elizabeth ) and there were still two or three new Atlantic liners either under construction or in the planning stage. Most of the world's passenger fleet was still steam powered, and there were still a lot of ships from the 1920s and 1930s in service. The Queen Mary was the most famous of all of them, but it wasn't exactly unique.

2. In 1967, the Queen Mary was only 31 years old. That was fairly old for a ship by the standards of the time, but not old enough to be an antique. There were still a lot of shops that age or older in service.

3. By the 1960s, the Art Deco style that flourished from the 1920s-1940s was out of style. The ship's interiors were just considered old, out of fashion, and out of date and not really worthy of preservation.

4. The manner in which the Tidelands funds had been appropriated required a substantial amount of rebuilding to house all the necessary functions inside the ship, since the existing layout of a passenger liner didn't automatically suit all the new roles.

That said, the original plans were actually a lot better than what was eventually done. The city contracted with the credit card company Diners Club Inc. as the ship's master lessee. Diners Club was responsible for building and operating the retail, dining, and banqueting operations and was also in charge of building out the hotel, which would then be turned over to a hotel management company to operate. Diners Club planned to use the main lounges on the upper decks for pre-dinner and after-dinner cocktails and entertaining, and use the main dining rooms on R Deck for the dining portion of events. Some public rooms on the upper decks would become shops or restaurants, and the 1 st Class swimming pool and most 2 nd Class public rooms would be reserved as hotel amenities.

For the museum part, the city brought in French undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau to develop the Cousteau Museum of the Sea. To create space, almost all of the below deck spaces would be gutted. Both turbo generator rooms, the water softening plant, all five boiler rooms, and the forward engine room were all ripped out, along with the watertight bulkheads between them. To raise the ceiling height for the museum, all of C Deck from stem to stern would be removed, more on that later.

Plans for the museum changed almost weekly as Cousteau kept coming up with wilder and more fantastical ideas (such as Plexiglas handrails with live eels swimming inside), which led to costly delays and constant design revisions. Ultimately, the money appropriated for the museum ran out and only a small portion of it was actually built and opened in 1972. Most of the space gutted to make room was sealed off and left abandoned and derelict. The truncated Museum of the Sea never met its attendance projections and closed permanently in around 1979, and the space was gutted again and converted to an exhibit hall.

In the meantime, the removal of C Deck created other issues (and not just the loss of the structural integrity of the ship's hull). C Deck was the main service area for the ship and housed things like storage rooms, workshops, laundry rooms, and the main kitchens. With it gone, all those functions would have to be replicated elsewhere on the ship. Diners Club proposed building new kitchens inside the funnel uptakes (with the boilers removed, the funnels were no longer needed to vent smoke, so the uptakes could be decked over on each level to create additional floor space). One set of kitchens on R Deck would supply the main dining rooms, and another set on Promenade Deck would handle the restaurants. However, Diners Club filed for bankruptcy in 1970 and divested its lease on the ship as part of the restructuring.

With the ship already way over budget and behind schedule, the city scrambled to find a replacement and brought in Specialty Restaurants Corporation of Los Angeles to replace Diners Club and get the ship ready to open with as little additional investment and in as little additional time as possible.

Specialty Restaurants cut a number of corners to save money and speed opening.

The kitchens on R Deck were cancelled and all banqueting functions would now be done in the upper deck lounges, with the restaurant kitchens now doing double duty. The Second Class and Third Class dining rooms were now unusable and were gutted and subdivided into storage and service spaces. The upper deck lounges had to be stripped of all their furniture and decorations so they could be set and reset for different events, and the storage requirements for folding tables and stacking chairs meant that smaller rooms, stairways, and halls had to be appropriated as storage space. To create individual outside entrances for each major room, smaller public rooms along the outside of the ship were carved up into hallways and lobbies. To make up for the loss of two major dining rooms, part of the enclosed promenade deck was subdivided into new meeting space.

In addition, only part of the ship was rewired. At sea, when the ship was generating it's own power, it used direct current (DC). Connected to the main electricity grid meant rewiring to alternating current.. To save money, only 5 of the 20 elevators on board were rewired. The rest were abandoned, which continues to create accessibility problems to this day, leading to Americans with Disabilities Act challenges.

Finally, the 1 st Class Swimming Pool that Diners Club wanted to save for hotel guests was rendered unusable by the gutting of C Deck below it, which removed the structural supports and caused it to sag under the weight of the water. Rather than pay to restructure it, Specialty Restaurants drained it and left it empty and derelict.

Work on the hotel kept getting postponed until a company could be found to manage it, and by the time Pacific Southwest Airlines signed on, the area earmarked for hotel use had been scaled back drastically. Most of the 2 nd Class amenities Diners Club wanted to keep for the hotel were gutted or converted to other uses, and the hotel opened in 1973 as basically two decks of rooms and little else.

With funds exhausted, plans to develop the surrounding 55 acres were also cut back. The large Visitors Center proposed for the site that would have also housed administrative offices was cancelled and those offices were relocated onto the ship, requiring more spaces to be gutted and reconfigured. A large convention hotel and a monorail connecting the ship with downtown Long Beach were also dropped. The shopping center was built, as a mock English Tudor village, but it failed after a few years and was mostly vacant by the 1990s and has since been mostly demolished.

Since the early 1970s, a succession of companies have operated the ship, but no large scale renovations or restorations have ever been carried out and the business model Specialty Restaurants put in place remains largely unchanged. Wrather Port Properties, the Walt Disney Company, and Queens Seaport Development have come and gone and all failed to earn any money on the operation.

So, what's left today?

First Class – 58% surviving

Preserved/Intact

1. Main Dining Room – banqueting ballroom called the Grand Salon

2. Main Lounge - banqueting ballroom called the Queen's Salon

3. Verandah Grill – banquet room

4. Main Entrance Hall and Shopping Centre – still used for original purpose

5. Smoking Room – banqueting ballroom called the Royal Salon

6. Swimming Pool – intact, vacant/derelict

7. Travel Bureau – static exhibit

8. Library – retail shop

9. Children's Playroom – retail shop

10.Drawing Room – retail shop

11.Radio Telephone Room – retail shop

Lost

1. Long Gallery and Midships Bar (including Boutique) – subdivided into two hallways, two meeting rooms, two storage rooms, a kitchen, and an entrance lobby for the Chelsea Chowder House restaurant

2. Cinema – incorporated into kitchens

3. Turkish Baths – gutted, storage space

4. Writing Room – public bathroom

5. Gymnasium – lower level incorporated into Hollywood Deli and Gallery, upper level turned into exhibit space

6. Barber Shop – office

7. Beauty Salon – office

8. Garden Lounge – incorporated into enclosed promenade deck

Second/Cabin Class – 20% surviving

Preserved

1. Main Lounge – banqueting ballroom called the Britannia Salon

2. Smoking Room – wedding chapel called Her Majesty's Royal Wedding Chapel

Lost

1. Library and Writing Room – subdivided into a storage room, a service pantry, and a hallway

2. Children's Playroom - incorporated into the Britannia Salon

3. Swimming Pool - subdivided into offices

4. Gymnasium – subdivided into offices

5. Main Dining Room – subdivided into a cold storage room, a laundry room, and an employee cafeteria

6. Main Entrance – used as employee/service entrance

7. Garden Lounge and Mermaid Bar – gutted, incorporated into the King's View Room and the Chelsea Chowder House restaurant

8. Barber Shop and Beauty Salon – mechanical room

Third/Tourist Class – 43% surviving

Preserved

1. Garden Lounge – meeting room

2. Main Lounge and Cinema – meeting room

3. Observation Bar – used for original purpose

Lost

1. Smoking Room – gutted, museum exhibit space

2. Children's Playroom – gutted, vacant

3. Synagogue – storage room (open to all classes, located in 3rd Class area)

4. Barber Shop and Beauty Salon- public bathroom

Powertrain – 25% surviving

Preserved

1. Aft Engine Room – static exhibit

2. Propeller Shafts – static exhibit

3. Steering Gear – static exhibit

Lost

1. Forward Engine Room – incorporated into exhibit hall

2. Aft Turbo Generator Room – incorporated into exhibit hall

3. Forward Turbo Generator Room – vacant/derelict

4. Water Softening Plant – incorporated into Dark Harbor attraction

5. Boiler Room 5 – incorporated into exhibit hall

6. Boiler Room 4 – vacant/derelict

7. Boiler Room 3 – vacant/derelict

8. Boiler Room 2 – incorporated into Dark Harbor attraction

9. Boiler Room 1 – incorporated into Dark Harbor attraction

With almost all other ships of this era long since scrapped, I guess we should be thankful the Queen Mary even survives at all, but still, it is a shame it hasn't been treated better and that so much of it is probably irretrievably lost.

Zipppy, Mazdurp builder, Probeski owner and former ricerboy

> ranwhenparked

Zipppy, Mazdurp builder, Probeski owner and former ricerboy

> ranwhenparked

10/04/2014 at 20:39 |

|

I went to the Queen Mary museum about 15 years ago, I might have to go back to remember it all.

Jcarr

> ranwhenparked

Jcarr

> ranwhenparked

10/04/2014 at 20:56 |

|

Awesome write-up. I've always been fascinated by luxury liners like the Queens, White Star triplets, etc.

ranwhenparked

> Jcarr

ranwhenparked

> Jcarr

10/04/2014 at 21:13 |

|

Me too. And there's a White Star tie-in with the Queens, of course. Cunard got a loan from the British government to complete the Queen Mary in exchange for agreeing to merge its transatlantic passenger services with the failing White Star Line, saving the government from having to bail them out in the event of their impending collapse. Most of White Star's aging and badly maintained ships were quickly retired, and the Queen Mary partially replaced the Olympic as well as her running mates Majestic (the Britannic replacement) and Homeric (the Titanic replacement).