by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/09/2017 at 10:33

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/09/2017 at 10:33

Tags: America

; Car industry

; Chevrolet

; Ford

; Chrysler

; Janis Joplin

; John Lennon

; Porsche

; Rolls Royce

; 1960s

; Culture

; Youth

STARS: 4

Disclaimer: This is an excerpt from my dissertation. I love cars so much I spent a year researching and writing 11,000 words, despite professors telling me it wouldn’t be considered a “legitimate” academic subject. Then, I bought a 1952 Chevrolet pickup as my daily driver.

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

Chapter Three:

1960 was the year of the styling shift and downsize. Several watershed moments coalesced almost simultaneously to crystallize the change. One of them was Bill Mitchell replacing Harley Earl as the styling director for General Motors. Another was a growing youth counterculture that took inspiration from a blossoming British Invasion among other European influences. Around this time, British musicians started to become popular in the US, with hit singles creeping into the top charts. Even the American music scene brought hints of Europe to motoring culture, in the form of Bob Dylan’s British motorcycles and Janis Joplin’s German cars. It was this year that the Big Three each introduced their take on the small car, and the first year that saw an absence of 1950s styling within their model lineups.

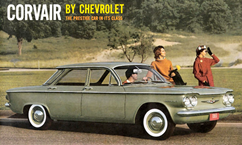

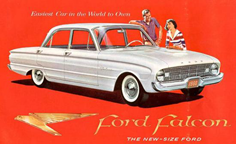

The Ford Falcon, Chevrolet Corvair, and Valiant (a Chrysler product) were all released in 1960, and were the Big Three’s first foray into the compact-car segment. Both the Falcon and the Valiant were front-engined, rear-wheel-drive machines, built for six people. The Corvair, on the other hand, resembled a well-known German auto in its rear-engined, air-cooled, rear-wheel-drive setup: the Volkswagen Beetle- hence its lack of a traditional front grille. Somewhat unsurprisingly (and in typical American fashion), the trio was not in direct competition with most of the European imports: “they [were] larger, faster, more expensive, more stylish”. [1] The Corvair was a striking departure from the 1959Chevrolet lineup stylistically- even the rest of the 1960 Chevrolets seem old-fashioned in comparison, although the year prior GM had cleaned up the front-end styling on several of its brands. The 1960 Falcon, unlike the Corvair, brought its crisp, elegant, and unfussy-yet-handsome design cues to the rest of the 1960 Fords, including an integrated headlight and grille feature and the deep, recessed “shoulder” line running the length of the car, looping in on itself at the front. The Valiant is the stylistic outlier of the three; it was designed by Virgil Exner who would not retire until 1961, and who left his 1950s aesthetic imprint on Chrysler products until (and a little beyond) that point. The machines produced under Elwood Engel, his successor, were much more modern. Nevertheless, the Big Three had each, simultaneously, made the first steps towards a more subtle, restrained, quiet, and smaller car, designed with greater honesty.

The 1960 Ford lineup was wonderfully cohesive, with each model sharing major design cues to create cars recognizably “Ford”. The grille and headlights were located on the same level, instead of the traditional headlight placement above the grille. This was something GM had dabbled with in1959, and would become a design feature on nearly everything the Big Three produced from then on. It contributed to a cleaner and simpler look- the headlights were less their own separate design feature, and so was the grille- compared to the 1958 Ford pictured on page nine, it looked much more modern. The side sculpturing is also of note: the ornamentation so characteristic of 1950sAmerican cars (look to the 1958 Buick on page sixteen for an example) had been dramatically reduced on these new Fords, replaced by working with the sheetmetal instead of tacking on bits of chrome. And, although it retained its fins, they were more vestigial now than they had ever been, and would soon disappear completely. Ford was the only one of the Big Three that did not have any major leadership overhauls in this period-their designers and executives were the same from the late-1950s through to the mid-1960s.

For Chevrolet (and the other GM lines), 1960 was the second, but largest step forward in GM’s march towards greater simplicity. The Corvair was a uniquely European car for GM at this time, and not just because of its mechanical layout. The single unbroken line running from headlight to taillight is reminiscent of that on the Volvo Amazon on page seventeen. The whole car is incredibly simply designed, but, through creasing and folding the body panels in a particular way, it is an interesting and compelling piece of rolling sculpture- a far cry from Maguire’s alleged “piece of soap”. The rest of the 1960 Chevrolets were the first to be untouched by the hand of Harley Earl, and were largely sculpted by Bill Mitchell. The Corvair was easily the most radically “new” looking out of the lineup, though, which would take two more years to fully shed itself of the last vestiges of 1950s design. Mitchell’s designs were typically much simpler and more restrained than Earl’s, with good bone structure and proportions- C. Edson Armi says his designs were “geared to European tastes”.

[1]

And certainly, the Corvair wore its body like a well-tailored British suit.

The Valiant’s design was definitely the least avant-garde of the three new Americans, and it was viewed as such at the time: European auto critics observed that “in the design of the Valiant there is no radical departure from established Chrysler practice”.

[1]

It would take until Exner’s retirement for the winds of change to blow at Chrysler, and even in the 1963 Dodges one can observe traces of the old guard in the rear end treatment. Elwood Engel’s move from Ford to Chrysler in1961 brought with it much of the fresh new Ford styling influence and sharp lines he learned while designing cars over there. Indeed, Robert Ackerson wrote that the 1963Chrysler 300J “relied upon a modern rendition of the British razor-edge design philosophy to achieve maximum visual effect”, because the era of fins and chrome had passed by the wayside.

[2]

A former colleague of Engel’s, George Walker of Ford, described Engel’s aesthetic as having “the concept of the nice, crisp line”.

[3]

The 300J, especially in its side profile, certainly has just that. Thus, for Chrysler and GM, new talent replacing old designers played a significant part in the shifting aesthetic.

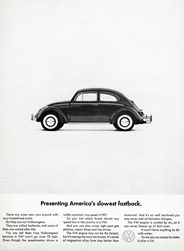

The products the Big Three put out post-1960 were very different from their previous efforts, and their advertising reflected that. To a certain extent, they took on some of the characteristics of European import advertising. Both Volvo and Volkswagen ran successful and iconic advertising campaigns in the late-1950s and early-1960s that utilized an element of self-deprecating humor and focused on appealing to practicality-minded customers, revealing the ideology behind the engineering of these cars. For instance, the VW ad “Presenting America’s slowest fastback” poked fun at recent developments in the US auto industry, which had been releasing aggressive models such as the Plymouth Barracuda and Ford Mustang (both of which were macho, performance machines designed to go far faster than laws allowed). The ad stressed mundane attributes of the VW- reliability, durability, economy, practicality, etc- and elevated those attributes above the frivolous focus on styling and speed that the Barracuda exemplified: hence the line “It won’t have anything to do with water. So we saw no reason to name it after a fish”.

[1]

Volvo, too, ran humorous advertisements such as “Drive it like you hate it”, which emphasized the impeccable build quality of the model, allowing it to function equally well as a safe family-carrier, a stable driver in snowy or off-road conditions, and a fun car to toss around with abandon (or, drive it like one hates it).

[2]

Although the new American advertisements did not have quite the same wit as the Europeans’, they did exhibit similar attentiveness to the practicality and functionality of the machines, while focusing less on their styling and emotional appeal. An advertisement for the 1960 Falcon is strikingly different from the older Ford advertisements with their unmitigated fixation on design and power; instead, it underlines roomy interior dimensions with maneuverable exterior dimensions, cheap running and purchasing costs, as well as its extensive development and testing (apparently three million miles worth). [1] Although it is perhaps obvious that an economy car would be marketed as such, this sort of advertising with its focus on sensibility percolated throughout model ranges: a 1961 Chevrolet advertisement for its full-size models shows exactly that. In it, Chevrolet touts “no needless bulk or ornamentation”, as well as a “contemporary-contoured rear deck”. [2] In another 1961 advertisement for the entire Chevrolet lineup, the highlight was how “sensationally sensible”, “useable”, “thrifty”, and “liveable” the new machines were after their facelift and downsize. [3]

Chrysler, too, seems to have become more practical when it came to both building and marketing their cars. Dodge ran a campaign that took inspiration from the tongue-in-cheek Volkswagen advertisements- one example depicts four women standing behind a folding dressing partition, and a 1963 Dodge behind them; the picture beneath it displays the women in the auto, speeding away.

[1]

The caption reads: “Pardon us while we slip into...something comfortable!”.

[2]

Even its relatively stark (compared to the Chrysler advertisement on page ten) aesthetic is reminiscent of the Volkswagen campaign that preceded it. This shift in advertising, shared between the Big Three, reflects a more mature product as well as an audience more receptive and attracted to practical cars that put other concerns ahead of styling. It shows that the design shift was not yet another surface-level trend, but a reaction to a shifting American culture that prioritized real, practical things over gimmicks sold to them by corporations. The Dodge advertisement talked about the roofline almost as a sacrifice- they went without a sporty, sloping roof in order to give more headroom to the passengers in back.

[1]

The reviews of these cars prove that the way they were advertised was accurate- they went beyond the old complaints of a poorly assembled, style-over-substance product. Take, for example, a 1963 review of the Pontiac Tempest, a compact car: “it’s finished and fitted so thoroughly and luxuriously that there’s none of the utilitarian stigma that kept many people away from the early compacts”.

[1]

Even the British, who had typically eschewed American metal, were favorably impressed with a mid-size 1963 Plymouth Fury, saying that it “feels far from a fish out of water” and that it “is a strong competitor in its class”.

[2]

These were two very smartly-designed machines,with squared-off bodywork creased strategically, handsome in an understated way.

Europeans were receptive to the changed styling as well; the introduction of the Falcon in 1960 brought praise for its “clean and uncluttered” exterior.

[1]

American publications started to lean transatlantic in their styling critiques, with some calling the 1964 Dodge Polara an improvement in “an area many felt was one of Dodge’s weak points last year”.

[2]

The 1963 Dodge pictured on page 22 (and above) still had one foot in the 1950s in terms of styling, but the 1964 model had moved on completely. Describing the old-fashioned styling as a “weak point” shows how American critics were becoming more receptive to the new aesthetic. In surveys of owners as well, people tended to be happier with the more restrained styling; many who had just bought a 1963 full-size Chevrolet reported to

Popular Mechanics

that compared to the late-1950s models, the design was much improved.

[1]

The sales data speaks for itself: each of the three small cars sold at least 190,000 units in their first year; each of the Big Three ventured further into developing small- and mid-sized cars; and between 1958 to 1965, total sales for each of the Big Three more than doubled.

[2]

[3]

[4]

The youth market had a lot to do with this. This demographic was coming of age while an emerging counterculture sprung up around and from them. In

Consumer Culture: A Reference Handbook

, Douglas Goodman and Mirelle Cohen observed the patterns of young people part of the counterculture: “hip consumers are anticonsumption, but they have been taught to express their attitudes through what they buy. They are rebels, but they have been taught to rebel against last year’s fashions and especially to rebel against the old-fashioned Puritanism and frugality of their parents”.

[1]

In essence, American youth were just as consumerist as their parents, but in a different way: they consumed in order to express individuality and authenticity, to show their indifference to the status-quo. Car manufacturers around the globe recognized this desire to be unique and to appear anti-consumerist and anti-materialist in adolescents, and acted accordingly.

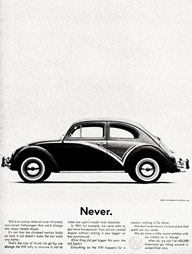

Volkswagen’s advertisements were designed to lure people into buying a Beetle by making them think they were independent-minded people with a grasp on what really mattered; their advertisement “Never” is the quintessential example of this. In it is pictured a Beetle with a two-toned chrome side profile, the caption reading “It’s not that the chromed version looks so bad; it just doesn’t make the car work any better...we change the VW only to improve it, not to make last year’s model look obsolete”. [1] Volkswagen’s portrayal of themselves as an honest and sensible company that does straight-deals with the customer is contrasted with their subtle attack on the typical business model of the domestic manufacturers. By depicting American car makers as conglomerates existing to exploit consumers, Volkswagen is implying that the reader has a choice: to blindly follow their materialism and love for frivolous embellishments, buy an American car, and thus support unscrupulous corporations; or to be a smart and moral consumer with an elevated awareness of political, social, and economic problems, with a superbly well-engineered machine to boot. This was a successful strategy- at the end of the advertisement, Volkswagen alluded to some 600,000 of their Beetles roaming America. [2]

The youth demographic, around which this counterculture centered, had become an important target for manufacturers to attract. The Pontiac Tempest Le Mans had American critics praising “all the youthful dash Pontiac’s been pushing in recent years”. [1] Advertising for the Tempest, which one Arizona dealership did in the form of a postcard pictured below, was suitably oriented. The Ford Mustang, which would hit the market less than a year after the Tempest, would follow the same engineering and marketing formula: a small, sporty car with a sharp and clean design, geared towards the young, with back-to-basics engineering- and it proved to be a runaway success, with more than 1,000,000 sold in the first year and a half of production. [2] According to Whiteley, a 1959 issue of Vogue observed “young” becoming the adjective to describe the latest and greatest in popular culture, and by 1963 “the media appeared to be obsessed with youth’s values, trends and idols”. [3] Britain in particular emerged as a fountain from which sprung art, design, music, and fashion to “worldwide acclaim”. [4] “Youth” had eclipsed the domain of the young and was becoming an aspiration for all ages.

American youth were the recipients of so much of this transatlantic culture. They were exposed to the music of

The Beatles

and

The Who

from the early 1960s, and, because many performances were televised, a visual aspect of music and musicians emerged. Photos of the bands, their hairstyles and fashions, and, of course, their preferred mode of transportation circulated far and wide. The visualization of celebrity culture undoubtedly influenced the purchasing decisions of impressionable youth. Take, for instance, Janis Joplin’s 1964 Porsche 356. A Porsche, then as now, was a luxury item; an expensive jewel of world-class development and expertise. Joplin, in an impressive feat of irreverence, had every square inch of hers painted in a psychedelic masterpiece, replete with prominently-featured psilocybin mushrooms, butterflies, and, weirdly enough, a cardiovascular system. While this was most likely done in some sort of expression of her personality, it also represented a blase attitude towards the established elite and, in certain ways, a sense of anti-materialism: after all, only one who does not put stock in the perception of high-status and serious-engineering attached to a Porsche will go on to paint it in such a “low-brow” fashion.

John Lennon, too, had a 1965 Rolls-Royce Phantom V which was painted in a vivid yellow, with brightly-colored floral motifs liberally festooned upon the exterior. Doing this to a Rolls-Royce is perhaps even more provocative than doing it to a Porsche- very few vehicles have quite the same level of prestige and imperious gravity attached to it than the dignified, stately Phantom V. Both of these cars were incredibly high-profile and appeared in countless photographs of the musicians- Joplin’s Porsche, especially, would be bombarded by fans in the San Francisco area, who would leave notes under the windshield wipers. [1] These paintjobs (among others, Keith Moon’s lilac-colored Rolls-Royce is another notable example) were proud demonstrations of individualism, but, more than that, they impertinently disregarded the connotations of elitism attached to the cars. By selecting expensive and “tasteful” examples of Europe’s finest, and then desecrating them with the symbolism and imagery of the counterculture- thus, in the process, eroding any status they once had- these musicians made a statement rejecting the pretension surrounding the machines.

This attitude, so widely broadcast the world over, made an impression upon youth: aspiring to own a Rolls-Royce or a Cadillac because of its social status was not what enlightened musicians like Lennon or Joplin would do. Although in many ways these rock-and-roll Rolls-Royces were just as ostentatious as the 1950s Motown metal they mocked, this was not a movement to combat self-centeredness (which seemed to be something of a hallmark of the 1960s), but rather to combat the importance attached to status and material wealth; the paintjob was very nearly the opposite of elitist. Youth were incredibly receptive to this message: even the miniskirt, one of the defining fashion items of 1960s teenagers, was named after the small and simple Mini Cooper. [1] Unpretentious cars engineered with integrity were in vogue with adolescent Americans of the early-1960s and represented their ethos.

The Big Three, to

capture the markets they were alienating in the 1950s and to appease the newly

emergent counterculture, had to send a message to consumers that they were

trustworthy companies making moral decisions. They did this by revising the design language of their products to

appear more honest. It helped, too, that

the Big Three was achieving greater success in foreign markets with their new,

downsized autos.

[2]

Thus, the more sensibly-styled (and sensible)

cars being put out by the Big Three not only assuaged the desires of a certain

part of the American public for a less outrageous form of transportation, but

they also reclaimed territory that had been lost during the era of Harley Earl’s

behemoths.

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Barry Miles,

The British Invasion: The

Music, The Times, The Era

, (Sterling Publishing Company Inc, 2009), p. 202

[2]

Road Test 1814

, p. 494

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Eric Russ,

Free Spirit: Janis Joplin’s Custom Porsche,

(Sotheby’s At Large, September 14

th

2015)

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Thom,

Pontiac Tempest

, p. 55

[2]

Mike Mueller,

Ford Mustang

, (MBI, 1997), p. 30

[3]

Nigel Whiteley, “

Semi-Works of Art”:Consumerism, Youth Culture and Chair Design in the 1960s

, (Furniture History, 23), p. 111

[4]

Ibid

, p. 111

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Volkswagen advertisement,

Never

, 1963

[2]

Ibid

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Mirelle Cohen and Douglas Goodman,

Consumer Culture: A Reference Handbook

, (ABC-CLIO, 2003), p. 54

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Jim Whipple,

Troubles Are Little for Owners of Big Chevrolets

, (Popular Mechanics, 115:2), p. 85

[2]

General Motors Heritage Center

[3]

Benson Ford Research Center

[4]

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles Historical Services

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Autocar road test 1771, Ford Falcon

, (The Autocar, April 29

th

1960), p. 700

[2]

Jim Wright,

Dodge Polara 500

, (Motor Trend, February 1964), p. 69

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Wayne Thom,

Pontiac Tempest Le Mans

, (Motor Trend, February 1963), p. 55

[2] Autocar road test 1932, Plymouth Fury , (The Autocar, July 19 th 1963), pp. 108-112

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Ibid

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Dodge advertisement,

Introducing the 1963 Dodge

, 1963

[2]

Ibid

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1] Ford advertisement, Introducing a wonderful new world of savings in the new-size 1960 Ford Falcon , 1960

[2] Chevrolet advertisement, New 1961 Chevrolet , 1961

[3]

Chevrolet advertisement,

A Whole Show in Itself!

, 1961

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Volkswagen advertisement,

Presenting America’s Slowest Fastback

, 1964

[2]

Volvo advertisement,

Drive it like you hate it

, 1962

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Road Test 1767, Chrysler Valiant

, (The Autocar, April 1

st

1960), p. 527

[2]

Robert Ackerson,

Chrysler 300: “America’s Most Powerful Car”

, (Veloce Publishing, 1996), p. 127

[3]

Railton,

Why Do Our Cars?

, p. 286

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Armi,

Car Design

, p. 58

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Railton,

Which Import?

, p. 97

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

08/09/2017 at 11:10, STARS: 0

As a note on the compacts competing with the VW in ‘60, Ford’s strategy in sales was to market the Falcon as being *more than* the VW for not much more cost. The front suspension was very softly sprung (with high preload to make it drivable) and it was touted as having “big car” ride quality. The light body is offset by very heavy door construction (Ford trademark “solidity”), and a host of options such as radio at minimal cost and automatic transmissions were designed to give it an edge. In the next few years this was enhanced by Futura trim models and the Pursuit 170 six and 260 V8 options.

There was one Falcon product that did have a price edge over VW, and that was the pickup. The Ranchero was cheaper than the VW cabover (even before the chicken tax) and cheaper than its stablemate cabover and the Corvair cabover. Ford gambled on many customers not needing more than 800lb carrying capacity.

"BritishLeyland™" (leylandcars)

"BritishLeyland™" (leylandcars)

08/09/2017 at 12:04, STARS: 0

“despite professors telling me it wouldn’t be considered a “legitimate” academic subject.”

Your so-called “professors” wouldn’t know a so-called “legitimate” academic subject if it jumped up and bit their asses!!!11

"d15b" (d15b7)

"d15b" (d15b7)

08/09/2017 at 14:53, STARS: 0

Well, I know what my bathroom reading material is. Thanks!