by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/04/2017 at 15:13

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/04/2017 at 15:13

Tags: America

; Europe

; Auto industry

; Chevrolet

; Ford

; Chrysler

; Reyner Banham

; Economy

; Culture

; 1950s

; 1960s

STARS: 3

Disclaimer: This is an excerpt from my dissertation. I love cars so much I spent a year researching and writing 11,000 words, despite professors telling me it wouldnt be considered a legitimate academic subject. Then, I bought a 1952 Chevrolet pickup as my daily driver.

Chapter Two:

In the late 1950s, there were few indications that the status-quo was about to be turned on its head. For the most part (barring a blip in 1958, the year of the Eisenhower Recession), car sales stayed strong despite remaining stylistically unchanged. Gross domestic product and personal consumption expenditures rose steadily throughout the decade, as did corporate profits, providing no hint that automobile styling would become plainer and more conservative- reflecting the opposite of how Americans were doing financially. [1] The space race and rapid pace of technological development stayed consistent, too. In an article published February 24 th , 1957, The Dallas Morning News claimed that automakers conducting market research to determine where to focus their efforts- on large or small bodies, powerful or efficient engines, outrageous or restrained styling- could not come to any sort of consensus on the matter. [2] Even within enthusiast circles, there was little agreement on the future of car design.

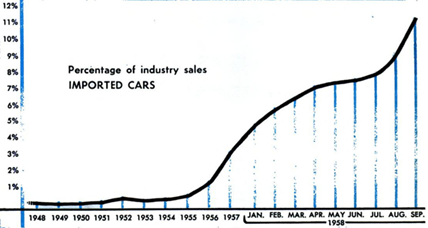

Signs cropped up now and again, however. In January of 1959, Art Railton of Popular Mechanics ran a recap of 1958 in cars: they noted the popularity of European import models in America, (cornering 11% of the market at one point), and a 30% dip in total industry sales. [1] On the reason why this phenomenon was occurring, the same Popular Mechanics article acknowledged a discrepancy in opinion between the manufacturers and industry critics: manufacturers blamed the Eisenhower Recession for creating a sales lag, while industry critics alleged the increasing opulence of American cars both outpriced (the 1957 models were, on average, 7.17% more expensive than the 1956 models) and morally repelled consumers. [2] [3] Railton saw the appeal of European cars, observing the glamor of the imported product...the wide variety of styling...[and] the variety of engineering that was absent from American machines. [4] He also noted that there were two models that, oddly enough, set sales records in 1958: the AMC Rambler and the Ford Thunderbird, both of which shared the distinction of being the smallest entrants in their respective classes. [5]

American owners of European imports were typically more pleased with their purchase than their fellow countrymen who had bought a domestic automobile.

[1]

Only in one area did Detroit have a perceived advantage over Europe: design. Railton described the Rambler American (a car nearly identical to the Nash Rambler pictured on page seven, and an example of European-inspired styling) as being not spectacular in either looks or performance, it is small, neat and practical.

[2]

In a different article published later in 1959, he alleged that styling matters less to the foreign car buyer than the domestic.

[3]

Even though the most common European import models were regarded as unstylish in the late 1950s, they still increased dramatically in popularity over the same time period- an indication of a looming backlash against the overtly (and perhaps overly) style-concerned American machines. Interestingly enough, a 1955 article in

Architectural Review

by renowned British design critic Reyner Banham discusses American public opinion concerning automobile styling:

When the American Ford Company issued a questionnaire to discover what qualities buyers sought in cars, most answerers headed their lists with such utilitarian considerations as road-holding and fuel consumption- a result which sales-analysis did not support- but when asked what

other people

looked for most headed their lists with chromium plate, colour-schemes and so forth.

[4]

Banhams observation touches upon something: the American auto-buying demographic were aware that purchasing decisions should not be influenced by surface-level superficialities, and knew that aesthetics were relatively unimportant compared to functionality. Little by little, proved in part by the increasing popularity of European cars, Americans were consuming with that in mind.

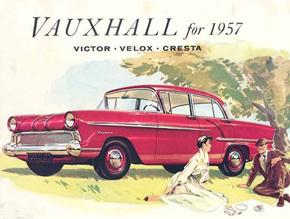

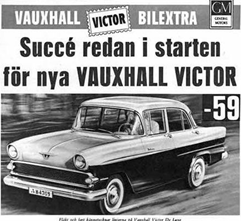

British enthusiast publications of the time shed light on the popular European auto aesthetic. The March 4 th , 1959 issue of The Motor magazine reviewed the Vauxhall Victor Series 2: the Victor as it was first revealed two years ago was so controversial in appearance that many people never even attempted to try its good qualities...the latest model looks more ordinary; a change which should have the beneficial result of introducing to a wider public a car that has been improved. [1] Pleasantly surprised by the refreshed styling, The Motor asserted the sheetmetal had been reworked to be cleaner, simpler, and less adorned. [2] As one can observe in the images below, the design revision replaced the two creases in the hood with one central one, simplified the front end styling, and took away some of the chrome and excessive surfacing on the sides to create a tidier and more cohesive appearance.

1957 and 1959 Vauxhall Victor advertisements, courtesy of Vauxhall Motors:

The resurfacing of the Victor could be interpreted as a step towards a more European style- fitting for Vauxhall, a British marque. There were hints that this design philosophy was permeating the US auto industry as well: Virgil Exner said in a 1959 interview that there is a very slow move towards greater simplicity in car design (288), and Elwood Engel said in the same interview that there has been a change since 1955 or so when people wanted lots of chrome and two and three-toning. They want it played down a little now, want it a little quieter.

[1]

Customers had been complaining that the all-consuming focus on styling sometimes

reduced

the actual functionality of the car: Double-wrap windshields cut into the roof, causing annoying reflections on the inside of the glass. Rear windows curve well up into the roof, exposing rear-seat riders to the summer sun like plants in a hothouse, and the corners of the wrap-around windshields banged knees upon entrance and egress.

[2]

On the 1958 Chevrolets, Fords, and Plymouths, the front-end styling incorporated potentially lethal design cues: Chevrolets are the most dangerous, being knife-edge wind splits that would slice into the flesh on impact. Plymouths are similar and only slightly less sharp. Fords are round but perhaps equally dangerous.

[3]

Years of sacrificing convenience and practicality for style no doubt contributed to the eventual adoption of a more European-inspired machine.

European auto design was typically more reliant upon a pure, organic form-following-function than its American counterpart- in many ways this lent the imports a more honest appearance than the domestics. A

Motor Life

review of a 1959 Cadillac corroborates this, observing that its distinctive features are largely on the surface, a matter of styling and appointments rather than extreme basic design.

[1]

Robert Maguire of Ford defended this practice, saying that Its easy to say cars are too big, too low or have too many fins. But take all the fins off and you end up with a piece of soap with wheels on it. Those fins finish off the metal, they give the full length to the car.

[1]

Maguires allegation is an argument without much merit; just a year after his statement, Ford redesigned their lineup to go without much of the tacked-on

accoutrements

they had- the new Fords were striking and had a purity of purpose in their metal that was missing from their forebears.

A survey of Studebaker Lark and AMC Rambler owners in 1958 reveals public malcontent with the auto industry. When asked what the Big Three should be doing, the overwhelming majority of owners (who seemed to be a largely wealthy and well-educated demographic) said that the manufacturers should focus less on styling and more on engineering a well-built, reliable, safe, and functional product.

[1]

Many of these owners were quite taken with the style of their European-inspired machines, saying they were stylish without being gaudy, not a mass of overhang and a mess of chrome, and, as a compliment, that they look British- especially the Lark.

[2]

These owners were displeased with the auto industry. for increasing the price, size, and visual ornamentation on cars without actually building a

better

car- and they represented a growing body of like-minded people. Fewer and fewer were willing to pay extra when all their money was going to was more chrome.

Whiteley alleges that towards the end of the 1950s, the yearly model change was the target of attack in America by the consumer protection movement: The consumer was depicted as being manipulated through psychological brainwashing into buying functionally inferior goods with built-in

physical

obsolescence which he or she did not actually need.

[1]

Consumers were beginning to realize that corporations had been, at the expense of benefits to functionality, pouring most of their money and efforts into superficial design changes. According to Rick Kranz, Robert McNamara created the

Market Research Unit

while he was working at Ford in the early 1950s, and quickly discovered that there was a market for small, inexpensive, and utilitarian cars in the US: the Big 3 identified two trends that showed a big market for small cars: 1. The number of licensed drivers would soar in the coming years. 2. Expanding prosperity would bring a dramatic increase of two-car families.

[2]

The demographic most interested was young, urban, educated, and wealthy- similar to the aforementioned Lark and Rambler owners.

[3]

There were two reasons for the focus on youth, Whiteley claims; the first is that they were the recipients of their parents disposable income (a not-inconsiderable amount of money for many), and the second is that as a demographic they were growing in numbers: around 20% from 1956-1963.

[4]

Even as far back as 1953 there was evidence that major automakers were pushing to appeal more to young people. This is disclosed in a letter from Zora Arkus-Duntov, known as the father of the Corvette, to Maurice Olley, a high-ranking engineer within Chevrolet. The letter is titled

Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot

Rodders and Chevrolet

, and contains an appeal to develop and market high-performance variants of engine parts- camshafts, valves, springs, manifolds, pistons and such- to compete with Ford, who was the sole provider of such goods.

[5]

Arkus-Duntov observed that magazines dedicated to hot-rodding were increasing rapidly in popularity, and were filled almost exclusively with content about Fords- this, he thought, meant when hot-rodders or hot-rod influenced persons buy transportation, they buy Fords. As they progress in age and income, they graduate from jalopies to second hand Fords, then to new Fords.

[6]

Auto manufacturers had recognized that the youth market was emerging quickly and growing exponentially, and were trying to capture it.

Not only were the Big Three looking to appeal more to American youth, they were also interested in pursuing foreign markets. A 1961 road test of a Buick Special in the British magazine

The Autocar

reveals these intentions:

During the last decade or so the products of Detroit, in the main, have gone through a period of grossness, which made them impractical for most European markets. Thus, although American cars enjoyed a wide popularity before World War II, there has been a big tumble in their overseas sales since then.

[7]

The period of grossness to which the author is referring made the cars Detroit produced simply too massive for the narrow roads typical of Europe. The second half of the 1950s saw the dimensions of the average domestic product grow enormously: The average 1957 car is 1.1 inches longer and 0.7 inch wider than the average 1956 car. Its 2.1 inches lower...From 1941 to 1955, average car length increased only 2.7 inches.

[8]

Fortunately, the US interstate system was created with the standards set forth in the 1956

Geometric Design Standards for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways

, which specified traffic lanes at least twelve feet wide.

[9]

But, because so much of Europes roadway network was built long before the automobile became a feature of daily life, many roads abroad were much narrower than this, leading drivers of American machines struggling to negotiate their way through medieval streets. Introducing smaller and more sensibly-styled cars would help American manufacturers recapture the European market and sell more vehicles.

The end of the 1950s did not see an obvious massive shift in American culture. The Space Race continued, as did the unprecedented economic growth. People were still buying and enjoying their be-chromed land-yachts, too. But enough small changes had occurred to make the Big Three sit up and take notice- and make a big change of their own. The murmurs of discontent at the crass consumerism auto makers were fostering with their yearly model change, frustration at paying more for the redesigns, the growing popularity of a (in many ways superior) European product, an emerging youth market with a unique attitude towards consumerism, and a potential European market all lead American car manufacturers to the inescapable conclusion that they could no longer continue business-as-usual.

[1]

Whiteley,

Throw-Away Culture

, p. 8

[2]

Rick Kranz,

As the 1950s end, âone size fits allâ strategy gives way to Falcon, other economy cars

, (Automotive News, June 16

th

2003)

[3]

Ibid

[4]

Whiteley,

Throw-Away Culture

, pp. 19-20

[5]

Zora Arkus-Duntov,

Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet

, December 16

th

, 1953

[6]

Ibid

[7]

Road Test 1814 Buick Special

, (The Autocar, March 31

st

1961), p. 494

[8]

Railton,

Listening Post

, p. 116

[9]

American Association of State Highway Officials,

Geometric Design Standards for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways

, (adopted July 12

th

1956, revised September 1

st

1956), p. 4

[1]

Art Railton,

These Cars Make Sense, Say Lark and Rambler Owners

, (Popular Mechanics, 111:5), pp. 84-85

[2]

Ibid

, pp. 248-250

[1]

Railton,

Why Do Our Cars?

, p. 178

[1]

1959 Cadillac and Imperial Road Test, (Motor Life, May 1959), p. 28

[1]

Railton,

Why Do Our Cars?

, pp. 178 and 288

[2]

Railton,

Parade

, pp. 294-296

[3]

Art Railton, PM

Tests the 1958 Chevrolet, Ford, Plymouth

, (Popular Mechanics, 110:1), p. 113

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

The Motor

, (March 4, 1959), p. 164

[2]

Ibid

, p. 164

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Arthur Railton,

Which Import is Best for You?

, (Popular Mechanics, 111:9), pp. 252-254

[2]

Railton,

Listening Post

, p. 154

[3]

Railton,

Which Import?

, p. 96

[4]

Reyner Banham,

The Machine Aesthetic

, (Architectural Review, April 1955)

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Art Railton,

Parade of Cars, 1959

, (Popular Mechanics, 111:1), p. 153

[2]

Ibid

, p. 153

[3]

Art Railton,

Detroit Listening Post

, (Popular Mechanics, 109:1), p. 116

[4] Ibid , p. 165

[5] Railton, Parade , p. 153

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1] United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, (bea.gov)

[2] Auto Market Analyses Contradict Each Other , (Dallas Morning News, (1957), p. 2

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

08/04/2017 at 15:31, STARS: 1

The 1958-60 Lincolns tried to have their cake and eat it too: a reduction in chrome and extent of fins, but some hyperactive futuristic styling touches and built on an enormous platform. They realized that the fin craze was eroding and tried to predict the next wave... somewhat badly. The 59, which was toned down from the 58, was marketed extensively with the phrase dramatically simple lines, in recognition that that was a potential edge. In an interesting twist, the 59 Continentals have *less* chrome than their Lincoln siblings.

Meanwhile, 1958 Chevies are a little odd because they (possibly) reduced fins too drastically, too fast. The fins on a 58 are not much more than styling flourish, but the 59 and the 60 return to rather dramatic forms as a last hurrah.

"Dash-doorhandle-6 cyl none the richer" (dash-doorhandle-and-bondo)

"Dash-doorhandle-6 cyl none the richer" (dash-doorhandle-and-bondo)

08/04/2017 at 16:42, STARS: 0

Im going to enjoy reading this. Had to re-read Deloreans chapter on the vega while working on a vega. It was as bad as Id heard.

"fintail" (fintail)

"fintail" (fintail)

08/04/2017 at 17:22, STARS: 0

This is interesting. It might also be something to study the metamorphosis (as I call it) car design of ~1960-64 or so and how it aligns with shifting social and political trends.