by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/04/2017 at 13:34

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

by "lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

Published 08/04/2017 at 13:34

Tags: America

; Car Industry

; Chevrolet

; Chrysler

; Ford

; Nash

; Studebaker

; Harley Earl

; Virgil Exner

; George Walker

; Design

; Culture

; 1950s

; 1960s

STARS: 4

Disclaimer: This is an excerpt from my dissertation. I love cars so much I spent a year researching and writing 11,000 words, despite professors telling me it wouldn’t be considered a “legitimate”¯ academic subject. Then, I bought a 1952 Chevrolet pickup as my daily driver.

Chapter One:

Over the course of the 1950s, American cars grew more and more fantastical in appearance, arguably culminating in the 1959 Cadillac, whose tailfins are pictured on the cover. Emblematic of 1950s American car design, the tailfin was first introduced in the 1948 Cadillac, and was inspired by a Lockheed P-38 Lightning observed by Harley Earl, the chief of styling for all GM products until 1959. [1] Tailfins were far from the only styling traits of these cars, though. Massive and ornate chrome grilles on both the front and rear were typical for the time, as were chrome spears scything across the sides, artistically formed hood ornaments (oftentimes there were three on a car: one large centerpiece, and two smaller decorations marking the front corners), curvy wraparound windshields, and two-tone paint schemes. As Whitely notes, “Instead of trying to attain a timeless and universal appearance...styling features expressed a strong commitment to contemporary ‘jet age’ advanced technology”¯. [2]

Besides

a few outliers, such as the Nash Rambler and some Studebakers (including the Champion

and the Lark), cars of the era were invariably enormous and exotic. Nash and Studebaker were both small players

in the industry, and they were the only ones offering small, light, and clean,

European-styled models. They achieved

limited success compared to the established players: in 1956, for instance,

Nash sold 79,166 Ramblers compared to Chevrolet’s 679,950 Biscaynes- enough to

establish that there was a market for smaller cars, but not enough to worry the

Big Three.

[1]

[2]

One of the most important designers in this period (and possibly the most important car designer of all time, practically inventing the concept of car styling in 1927) was Harley Earl. [1] According to Chuck Jordan, a retired Chief Designer for GM, “Earl’s creed had always been ‘longer, lower, wider’”¯. [2] Earl designed vehicles for GM from 1927 to his retirement in 1959, and developed his own, unique style throughout this period. [3] David Gartman, in an essay for Design Issues , wrote of Earl’s “auto-as-entertainment aesthetic...chrome encrustation...[and] rounded, heavy-looking cars”. [4] C. Edson Armi connected accounts of Earl’s 6'4” stature, flamboyant fashion sense, and booming, angry personality to the machinery he designed. [5] Interestingly enough, Earl did not know how to draw or how to model clay- those were the jobs of his subordinates- he had an incredible eye for design, however, and was a persuasive salesman to senior management. [6]

Virgil Exner was Earl’s counterpart at Chrysler. Exner, according to Grady Gammage Jr. and Stephen Jones, “constantly [claimed] that auto stylists responded only to the dictates of public taste”¯, and his designs apparently resulted in the nickname “Virgil Excess”. [1] Indeed, in an interview with Arthur Railton for Popular Mechanics , Exner maintains that “the public has indicated its preference for larger packages throughout the years, through sales experiences. Stylists don’t want a lot of chrome either. But people have demanded it through the years”¯. [2] This was similar to Earl’s design philosophy, described by some as “production and sale oriented”. [3] While Exner acknowledged that a car was first and foremost designed for transportation, he felt strongly that “It should create a desire for ownership and a pride of ownership. A person is looking for something with a feeling of motion that inspires him”¯. [4] Styling that brought character and emotion to the forefront was crucial on Exner’s Chryslers.

George Walker was the public face of Ford styling. In the same interview for Popular Mechanics , he described the American consumer as “aggressive, it’s moving upward all the time. The average man still likes that up, up, up, and that means bigness”, referring to what size cars are popular. [1] He also talked about the low-slung silhouette on Fords of the day, and the ever-present debate on practicality versus style: “When you think of an automobile, you think of movement and that means aerodynamics...How many times a day does a person get in and out of a car? We say...about four times a day. Why would he forsake good silhouette just because he knocks his hat off a few times a day?”¯. [2] In Walker’s mind, a car needed to be styled with emotion in order to achieve sales targets. The aesthetics of these three men had a significant effect on the final shapes their machines took, but the tastes of the consuming public played an equally important part.

The

advertising of these cars is highly indicative of what The Big Three thought of

their creations and what they thought the American public wanted from their

creations. An advertisement on this page

for the 1958 Chevrolet lineup reveals a pretty much exclusive focus on styling

and power. They describe the models as “sports-minded,

fun-hearted and beautiful as all outdoors...[with] prices as low as Chevy’s

roofline!”¯.

[1]

There are several paragraphs that do little

more than describe the design and sportiness of the cars, without any mention

of practicality, economy, or reliability. Chevrolet’s advertising in the late 1950s

appealed primarily to the emotional purchaser. The illustrations capture two-toned examples of their cars from the

exterior, showing the reader how dynamic the styling is without providing any

real information.

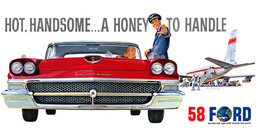

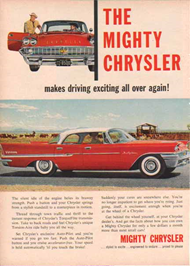

The story is much the same with Chrysler’s and Ford’s advertising campaign at the end of the decade. Chrysler focused on their luxuriously vast interiors and how well their cars drove; “just going, itself, is excitement enough when you’re at the wheel of a Chrysler!”- to the exclusion of any quantitative information on fuel economy, price, or power. [1] The focus on space as representative of luxury is telling of the “more is better”¯ philosophy behind many of these autos- Chrysler did not mention the quality of the materials used on their interiors, they instead described “living-room proportions” as a desirable attribute of their cars. [2] Ford, for their part, took seducing the emotional purchaser to its logical conclusion, and published advertisements that pictured their products with jet planes and elegantly dressed people, headed with taglines like “The world’s most perfectly proportioned cars”¯, or “Hot, handsome...a honey to handle”¯. [3] [4] Aesthetics and driving pleasure were the primary attributes The Big Three focused on developing in their machines, in part because they were the attributes they thought appealed most to the American buyer. The American consumer’s tendency to buy based on emotion is thus reflected in the designs of these cars.

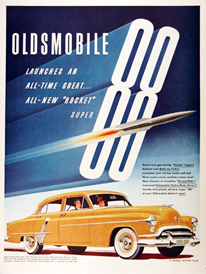

Part of the success of the emotional styling and advertising of these cars (and successful they were- The Big Three routinely sold more than a million each in a year) was down to the post-war cultural climate in America. Whiteley links the 1950s design language to the prominence of technology and power in post-war society, when the manufacturers aimed to evoke space exploration and fighter jets in their cars. [1] Raymond Loewy, a famous industrial designer (who penned many of Studebaker’s post-war designs), phrases it somewhat less graciously in a 1955 article for The Atlantic : “Nothing about the appearance of the 1955 automobiles offsets the impression that Americans must be wasteful, swaggering, insensitive people”¯. [1] Here is a correlation between culture and consumption: American culture at the time was being shaped by the space race and associated rapid technological advancements. Late-1950s car design exhibits this proudly: the tailfins, the long and pointy chrome decorations, and the cockpit-like surround of the windshields are all meant to conjure up fantasy images of jets and rockets. Oldsmobile’s advertising series for their Rocket 88 model exploited this concept, and Chevrolet, too, advertised their 1955 Bel Air with jet planes in the background, in an allusion to the prodigious power underneath the hood. [2] Even the names of various models link them to space and travel: Galaxie, Starfire, Sunliner, Comet, Nova, etc). [3]

The financial climate of post-war America left

its own imprint on domestic sheetmetal: the way these machines unashamedly wore

their chrome jewelry quite literally puts on display the fortune of the driver,

and reflects not just a possession of wealth but a desire to flaunt it. After World War II, about half the population of

America saw a wild increase in wealth.

[1]

Grady Gammage Jr. and Stephen Jones link the

outrageous styling of the 1950s to “the social and economic factors of given

years...Fins caught the imagination of a public trying to forget the deprivation

of the war”¯.

[2]

In a study of consumer habits, Shelley Nickles notes that “consumer research revealed that the working-class masses generally

believed worth was expressed through three design features. One was ‘bulk and size’...Another was ‘embellishment and visual flash’. The

third was color”¯.

[1]

Because these masses were the ones benefiting

most from the post-war American bull economy and were the largest consumer

demographic, the majority of The Big Threes efforts went towards creating a product

for them and their tastes.

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

Even the showroom sales

tactics for these models were focused around appearance. A 1957 bulletin for Plymouth salesmen illustrates

the single-mindedness of the tactic:

Plymouth is over 4 inches wider and nearly 4 inches lower than Chevrolet- but styling lines make the difference appear even greater. Plymouth’s smoothly upswept fins add beauty...don’t “box in” the rear of the car like Chevrolet’s squared-off fenders. And notice the graceful slope of Plymouth’s deck lid compared to the sudden drop-off of the high, squarish Chevrolet deck lid...Plymouth styling lines are lower and more modern! [1]

Not

only does this bulletin show that style in general was crucial to selling a model,

it also shows that the outrageous 1950s aesthetic was the exact

type

of style that sold. A review of the 1956 Corvette by Karl

Ludvigsen in

Sports Cars Illustrated

discloses

deep admiration for the design, described as “a real traffic-stopper...The hood

bulges, long fender lines, and cowl vents...combine to give an impression of

great forcefulness”.

[1]

The two-tone paint jobs of these early

Corvettes, along with the scalloped-out sides with chrome surrounds, prominent

grilles, and pontoon-style rear fenders were all flashy and in-your-face design

elements- but that was what worked for American consumers.

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Karl Ludvigsen,

1956 Chevrolet Corvette

Road Test

, (Sports Cars Illustrated, May 1956).

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Ross Roy Confidential Bulletin for Plymouth Salesmen,

Plymouth vs. Chevrolet

, (Plymouth Bulletin, 6), p. 3

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Shelley Nickles,

More is Better: Mass

Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America

, (American

Quarterly, 54:4), p. 588

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Whitely,

Throw-Away Culture

, p. 5

[2]

Gammage Jr. and Jones,

Orgasm in Chrome

,

p. 132

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Raymond Loewy,

Jukebox on Wheels

,

(The Atlantic, 1955)

[2]

Chevrolet Advertisement,

Chevrolet’s

3

new engines

put new fun under your foot!

, 1955

[3]

Oldsmobile Advertisement,

Oldsmobile

Launches an All-Time Great, All-New ‘Rocket’ Super 88

, 1953

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Whiteley,

Throw-Away Culture

, p. 6

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Chrysler advertisement,

The Mighty

Chrysler Makes Driving Exciting All Over Again!

, 1958

[2]

Chrysler advertisement,

Swing in...stretch

out, revel in Chrysler Roominess!

, 1959

[3]

Ford advertisement,

The world’s most

beautifully proportioned cars

, 1959

[4]

Ford advertisement,

Hot, handsome...a honey

to handle!

, 1958

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Chevrolet advertisement,

Nothing goes

with springtime like a bright new Chevy!

, 1958

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Ibid

, p. 282

[2]

Ibid

, p. 176

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Grady Gammage Jr. and Stephen Jones,

Orgasm

in Chrome: The Rise and Fall of the Automobile Tailfin

, (The Journal of

Popular Culture, 8:1), p. 138

[2]

Arthur Railton,

Why Do Our Cars Look the

Way They Do?

, (Popular Mechanics, 111:1), p. 179

[3]

Gammage Jr. and Jones,

Orgasm in Chrome

,

p. 135

[4]

Railton,

Why Do Our Cars?

, p. 177

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Interview: Chuck Jordan, GM’s Chief Designer

,

(Motor Trend, June 2006)

[2]

Ibid

[3]

Ibid

[4]

David Gartman,

Harley Earl and the Art

and Color Section: The Birth of Styling at General Motors

, (Design Issues,

10:2), p. 25

[5] C. Edson Armi, The Art of American Car Design: The Profession and Personalities , (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), p. 26

[6] Ibid , p. 32

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

John Gunnell,

Standard Guide to 1950s

American Cars

, (Krause Publications, 2004), p. 170

[2]

General Motors Heritage Center

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

[1]

Karal Ann Marling,

America’s Love Affair

with the Automobile in the Television Age

, (Design Quarterly, 146), p. 8

[2]

Whitely,

Throw-Away Culture

,

p. 11

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

08/04/2017 at 13:51, STARS: 0

What I find amusing about the end of that era at Ford, is that the McNamara-driven drive back toward cheapness and (to a point) practicality failed to stamp out the fantastic tendencies of the designs ; the outrageousness just got model-segregated (Thunderbird) and sublimated in “sneaky” ways. It went underground.

What, I wonder, is the styling impetus for the new, better, disposable Ford of 1960, I wonder? Let’s look:

Something familiar about that side shape. ENHANCE:

Oh.

Well, that explains the rocket/jet exhaust taillights, then. The motif of which was on every single Ford non-truck model up to ~’65.

"RallyWrench" (rndlitebmw)

"RallyWrench" (rndlitebmw)

08/04/2017 at 14:15, STARS: 0

I’ll come back to read this in full later, thanks.

"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

08/04/2017 at 14:26, STARS: 0

MacNamara actually came into those executive, decision-making positions at Ford right when they were releasing their cheaper, more practical models. Always found it weird that the Thunderbird looked so different from the rest of their lineup. But those ‘64 Galaxie taillights are just perfect.

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

"RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht" (ramblininexile)

08/04/2017 at 14:35, STARS: 0

I know that MacNamara was part of something of a faction at Ford lobbying for an everyman car, and pushed for the sidelining of such things as the big Lincolns in favor of streamlining. Mostly winning out.

By ‘63 Ford had, however, realized that the Thunderbird was as near to being a mascot as anything they had - an attainable halo car - so the marketing for the ‘63 fullsize Fords went hell for leather pushing Thunderbird connections. “Thunderbird package” engines. 500XL buckets “like in the Thunderbird”, swing-away steering column “as found in the Thunderbird”, “Thunderbird style compliance link” on the front suspension, etc. etc. etc.